CASE Feeling hopeless

Dr. D, age 33, a white, male physician, presents with worsening depression, suicidal ideation, and somatic complaints. Dr. D says his personal life has become increasingly unhappy. He describes the pressures of a busy practice and conflict with his wife about his availability to her. He is feeling financial pressure and general disappointment about practicing medicine. Lack of recreational activities and close friends and absent spiritual life has led to feelings of isolation and depression.

Dr. D reports difficulty falling asleep, waking up early, and feeling fatigued. He describes obsessive, negative thoughts about his work and his personal life; he is anxious and tense. Dissatisfied and exhausted, he says he feels hopeless and empty and has become preoccupied with thoughts of death.

Dr. D describes musculoskeletal tension in the neck, shoulders, and face, with pain in the back of the neck. When the depressive symptoms or pain are particularly severe, he admits that his attention to critical information lapses. When interacting with his patients, he has missed important nuances about medication side effects, for example, frustrating his patients and himself.

Dr. D and his wife do not have children. His mother and paternal grandfather had depression, but Dr. D has no family history of suicide or drug or alcohol abuse. He has no significant medical conditions, and is not taking any medications. Dr. D drinks 1 or 2 cups of caffeinated coffee a day. He does not smoke, use recreational drugs, or drink alcohol regularly.

What would be your next step in treating Dr. D?

a) alert the state medical board about his suicidal ideation

b) recommend inpatient treatment

c) refer Dr. D to a clinician who has experience treating physicians

d) formulate a suicide risk assessment

The authors’ observation

Assessment of the suicidal physician is complex. It requires patience and ability to understand the source and the extent of the physician’s desperation and suffering. Not all psychiatrists are well suited to working with patients who also are peers. An experienced clinician, who has confronted the challenges of practice and treated individuals from many professions, could be better equipped than a recent graduate. Physician− patients might not be forthcoming about the extent of their suicidal thinking, because they fear involuntary hospitalization and jeopardizing their career.1

The evaluating clinician must be thorough and clear, and able to facilitate a trusting relationship. The ill physician should be encouraged to express suicidal ideation freely—without judgments, restrictions, or threats—to a trusted psychiatrist. Questions should be clear without possibility of misinterpretation. Ask:

• “Do you have thoughts of death, dying, or wanting to be dead?”

• “Do you think about suicide?”

• “Do you feel you might act on those thoughts?”

• “What keeps you safe?”

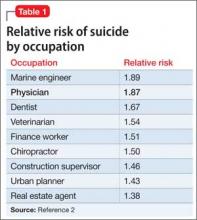

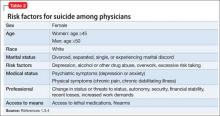

Physicians and other health professional have a higher relative risk of suicide (Table 1).2 Hospitalization should be considered and the decision based on the severity of the illness and the associated risk. Dr. D has several risk factors for suicide, including marital discord, pain, professional demands, and access to lethal means (Table 2).1,3,4

HISTORY Pain and disappointment

After medical school, Dr. D completed residency and joined a large clinic with outpatient and inpatient services. His supervisor was pleased with his work and encouraged him to take on more responsibility. However, within the first years of practice, his mood slowly deteriorated; he came to realize that he was deeply sad and, likely, clinically depressed.

Dr. D describes his parents as detached and emotionally unavailable to him. His mother’s depression sometimes was severe enough that she stayed in her bedroom, isolating herself from her son. Dr. D did not feel close to either of his parents; his mother continued to work despite the depression, which meant that both parents were away from home for long hours. Dr. D became interested in service to others and found that those he served responded to him in a positive way. Service to others became a way to feel recognized, appreciated, respected, and even loved.

Dr. D’s depressive symptoms became worse when he discovered his wife was having an affair. The depression became so debilitating that he requested, and was granted, an 8-week medical leave. Once away from the daily pressures of work, his depression improved somewhat, but conflict with his wife intensified and thoughts of suicide became more frequent. Soon afterward, Dr. D and his wife separated and he moved out. His supervisor recommended that Dr. D obtain treatment, but it was only after the separation that Dr. D decided to seek psychiatric care.