Similar to TD, withdrawal dyskinesia can present in different forms:

• tongue protrusion movements

• facial grimacing

• ticks

• chorea

• tremors

• athetosis

• involuntary vocalizations

• abnormal movements of hands and legs

• “dyspnea” due to involvement of respiratory musculature.5,11

There may be a sex difference in duration of withdrawal dyskinesias, because symptoms persist longer in females.9

Although covert dyskinesia also develops after discontinuation or dosage reduction of a dopamine-blocking agent, the symptoms usually are permanent, and could require reintroducing the antipsychotic or management with evidence-based treatments for TD, such as tetrabenazine or amantadine.6,12

What is the cause of Ms. X’s abnormal involuntary movements?

a) quetiapine-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

b) aripiprazole-induced cholinergic overactivity

c) quetiapine-induced cholinergic overactivity

d) aripiprazole-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

The authors’ observations

Pathophysiology of this condition is unknown but different theories have been proposed. D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity to compensate for chronic D2 receptor blockade by antipsychotics is a commonly cited theory.7,13 Discontinuation of an antipsychotic can make this D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity manifest as withdrawal dyskinesia by creating a temporary hyperdopaminergic state in basal ganglia. Other theories implicate decrease of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the globus pallidus (GP) and substantia nigra (SN) regions of the brain, and oxidative damage to GABAergic interneurons in GP and SN from excess production of catecholamines in response to chronic dopamine blockade.14

It has been proposed that patients with withdrawal dyskinesia might be in an early phase of D2 receptor modulation that, if continued because of use of the antipsychotic implicated in withdrawal dyskinesia, can lead to development of TD.4,7,8 A feature of withdrawal dyskinesia that differentiates it from TD is that it usually remits spontaneously within several weeks to a few months.4,7 Because of this characteristic, Schultz et al8 propose that, if withdrawal dyskinesia is identified early in treatment, it may be possible to prevent development of persistent TD.

Look carefully for dyskinetic movements in patients who have recently discontinued or decreased the dosage of their antipsychotic. Non-compliance and partial compliance are common problems among patients taking an antipsychotic.15 Therefore, careful watchfulness for withdrawal dyskinesias at all times can be beneficial. Inquiring about recent history of these dyskinesias in such patients is probably more useful than an exam because the dyskinesias may not be evident on exam when these patients show up for their follow-up visit, because of their self-limited nature.8

Treatment options

If a patient is noted to have a withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia, a clinician has options to prevent TD, including:

• decreasing the dosage of the antipsychotic

• switching from a typical antipsychotic to an atypical antipsychotic

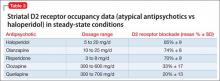

• switching from one atypical to another with lesser affinity for striatal D2 receptor, such as clozapine or quetiapine.16,17

In addition, researchers are investigating the use of vitamin B6, Ginkgo biloba, amantadine, levetiracetam, melatonin, tetrabenazine, zonisamide, branched chain amino acids, clonazepam, and vitamin E as treatment alternatives for TD.

Tetrabenazine acts by blocking vesicular monoamine transporter type 2, thereby inhibiting release of monoamines, including dopamine into synaptic cleft area in basal ganglia.18 Clonazepam’s benefit for TD relates to its facilitation of GABAergic neurotransmission, because reduced GABAergic transmission in GP and SN has been associ ated with hyperkinetic movements, including TD.14Ginkgo biloba and melatonin exert their beneficial effects in TD through their antioxidant function.14

The agents listed in Table 219 could be used on a short-term basis for symptomatic treatment of withdrawal dyskinesias.1,18,20

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been reported with aripiprazole discontinuation and is thought to be related to aripiprazole’s strong affinity for D2 receptors.21 Aripiprazole at dosages of 15 to 30 mg/d can occupy more than 80% of the striatal D2 dopamine receptors. The dosage of ≥30 mg/d can lead to receptor occupancy of >90%.22 Studies have shown that EPS correlate with D2 receptor occupancy in steady-state conditions, and occupancy exceeding 80% results in these symptoms.22

Compared with aripiprazole, quetiapine has weak affinity for D2 receptors (Table 3), making it an unlikely culprit if dyskinesia emerges within 2 weeks of initation.22 We believe that, in Ms. X’s case, quetiapine might have masked the severity of aripiprazole withdrawal dyskinesia by causing some degree of D2 receptor blockade. It may have decreased the duration of withdrawal dyskinesia by the same effect on D2 receptors. It may have lasted longer if aripiprazole was not replaced by another antipsychotic. This is particularly evident because dyskinesia improved quickly when quetiapine was titrated to 150 mg/d. The higher quetiapine dosage of 150 mg/d is closer to 5 mg/d of aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy and affinity. However, quetiapine is weaker than aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy at all dosages, and therefore less likely to cause EPS.16

Summing up

Withdrawal dyskinesia in the absence of a history of TD is a common symptom of antipsychotic discontinuation or dosage reduction after long-term use of an antipsychotic. It is more commonly seen with antipsychotics with high D2 receptor occupancy, and has been hypothesized to be related to D2 receptor supersensitivity to ambient dopamine, resulting as a compensatory response to chronic D2 blockade by this class of medication.