It seems like common sense: Sleeping poorly results in not feeling good. The truth is that many of our patients are sleep deprived but are either unaware of, or unwilling to acknowledge, their problem. The busy life that many patients have does not allow adequate time for sleep. In fact, I have encountered patients who think of sleep as an inconvenience that takes away time from other pursuits.

Sleep deprivation in psychiatric disorders

Sleep deprivation occurs when the duration or quality of sleep is inadequate. Inadequate sleep duration can be caused by insomnia or simply not allowing enough time for sleep (1 aspect of poor sleep hygiene). Poor sleep quality often is caused by sleep-disordered breathing.

Sleep deprivation can result in either sleepiness or fatigue. Sleepiness is a propensity to fall asleep; fatigue is a lack of energy that is not alleviated by additional sleep. Fatigue is more likely to be associated with a psychiatric disorder; sleepiness is more predominant in sleep disorders (although there is significant overlap). For example, patients with a major depressive disorder can experience fatigue as much as patients with sleep deprivation, but the latter also is more likely to result in sleepiness. Trouble concentrating is seen in anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and sleep deprivation.1

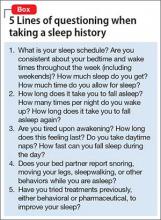

Insomnia or poor sleep hygiene can be diagnosed with a thorough sleep history. I take special care to consider sleep problems by presenting 5 groups of questions to the patient (Box).

Sleep-disordered breathing

A sleep study is required to accurately diagnose sleep-disordered breathing. Unless this diagnosis is specifically looked for, it remains hidden from both physicians and patients. Clues to the presence of sleep-disordered breathing include snorting, snoring, and gasping for air during sleep; witnessed apnea during sleep; nighttime awakening; daytime fatigue; nocturia; mouth breathing or dry mouth; acid reflux; irritability; morning headache; nighttime sweating; and low libido. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing include obesity; smoking; menopause; family history; increasing age; and anatomical factors (eg, deviation of the nasal septum; retrognathia; long face syndrome; high-arched narrow hard palate; large tonsils, uvula, or tongue).2

Measuring sleep quality

Some patients are unaware of the extent to which they are sleepy. The most widely used scale to measure sleepiness is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.3 Sleep specialists view a score of ≥10 on the Epworth scale as indicative of daytime sleepiness. In addition, a patient’s daily consumption of caffeinated beverages can be a clue to excessive sleepiness or, at least, fatigue. If the degree of sleepiness cannot be determined subjectively, objective measures, such as the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT), can quantify it. In a randomly selected sample from the general population, 13.4% had excessive daytime sleepiness as measured by the MSLT.4

Adult ADHD and sleep deprivation

In my practice, sleep problems confound both the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders, especially ADHD. Often, patients who report ADHD symptoms have no clear history of ADHD during childhood. In these cases, I always consider the possibility that their ADHD symptoms are due to sleep deprivation. Sleep deprivation can mimic the poor executive function and difficulty concentrating that is often seen in ADHD, because such deprivation is associated with decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex during wakefulness.5

In patients who provide a clear history of ADHD symptoms during childhood, it is possible that inadequate sleep exacerbates ADHD symptoms as adults. Unless sleep deprivation is diagnosed and treated in these patients, they can end up taking a higher-than-necessary dosage of a stimulant. Also, patients who have ADHD might have a difficult time managing their sleep schedule because of poor executive functioning. This, in turn, can result in additional sleep deprivation, thus worsening their ADHD symptoms, creating a vicious circle.

Psychotropics and sedation

Many psychiatric medications list sedation as a side effect. Patients with untreated sleep problems might be more likely to notice this side effect because sleep problems contribute to their fatigue. I have had patients who were unable to tolerate sedative medications until their sleep apnea was treated.

In conclusion

It is important to consider sleep deprivation in your differential diagnosis of psychiatric patients. This will allow for more accurate diagnosis and treatment and, in some cases, can avoid treatment resistance.