Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) is a disorder of affective expression that manifests as stereotyped and frequent outbursts of crying (not limited to lacrimation) or laughter. Symptoms are involuntary, uncontrolled, and exaggerated or incongruent with current mood. Episodes, lasting a few seconds to several minutes, may be unprovoked or occur in response to a mild stimulus, and patients typically display a normal affect between episodes.1 PBA is estimated to affect 1 to 2 million people in the United States, although some studies suggest as many as 7 million,1,2 depending on the evaluation method and threshold criteria used.3

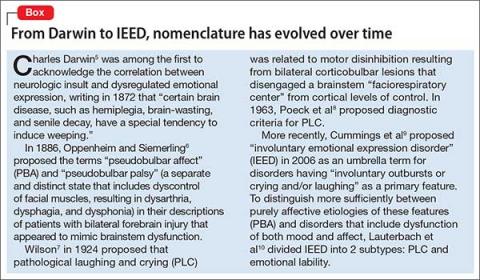

Many terms have been used to describe aspects of PBA (Table 14 and Box5-10). This abundance of often conflicting terminology is thought to have impeded efforts to categorize emotional expression disorders, determine their prevalence, and evaluate clinical evidence of potential therapeutic options.1Where to look for pseudobulbar affect

PBA has been most commonly described in 6 major neurologic disorders:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

- multiple sclerosis (MS)

- Parkinson’s disease

- stroke

- traumatic brain injury (TBI).

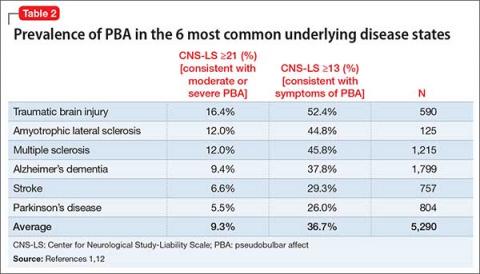

Of these disorders, most studies have found the highest PBA prevalence in patients with ALS and TBI, with lesser (although significant) prevalence in Parkinson’s disease (Table 2).1,12 These “big 6” diagnoses are not a comprehensive list, as many other disease states are associated with PBA (Table 3).12-14

As PBA has become better defined and more widely recognized, additional sequelae have been described. PBA’s sporadic and unpredictable nature and the potential embarrassment and distress of public outbursts may lead to an agoraphobia-like response.15 People with PBA report a significantly worse subjective assessment of general health, quality of life, relationships, and work productivity compared with people with similar primary underlying diagnoses without PBA.162 Pathways: ‘Generator’ and ‘governor’

Despite the many and varied injuries and illnesses associated with PBA, Lauterbach et al10 noted patterns that suggest dysregulation of 2 distinct but interconnected brain pathways: an emotional pathway controlled by a separate volitional pathway. Lesions to the volitional pathway (or its associated feedback or processing circuits) are thought to cause PBA symptoms.

To borrow an analogy from engineering, the emotional pathway is the “generator” of affect, whereas the volitional pathway is the “governor” of affect. Thus, injury to the “governor” results in overspill, or overflow, of affect that usually would be suppressed.

The emotional pathway, which coordinates the motor aspect of reflex laughing or crying, originates at the frontotemporal cortex, relaying to the amygdala and hypothalamus, then projecting to the dorsal brainstem, which includes the midbrain-pontine periaqueductal gray (PAG), dorsal tegmentum, and related brainstem.

The volitional pathway, which regulates the emotional pathway, originates in the dorsal and lateral frontoparietal cortex, projects through the internal capsule and midbrain basis pedunculi, and continues on to the anteroventral basis pontis. The basis pontis then serves as an afferent relay center for cerebellar activity. Projections from the pons then regulate the emotional circuitry primarily at the level of the PAG.10

Lesions of the volitional pathway have been correlated with conditions of PBA, whereas direct activation of the emotional pathway tended to lead to emotional lability or the crying and laughing behaviors observed in dacrystic or gelastic epilepsy.10 The pivotal nature of the regulation occurring at the PAG has guided treatment options. Neurotransmitter receptors most closely associated with this region include glutamatergic N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), muscarinic M1 to M3, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-A, dopamine D2, norepinephrine α-1 and α-2, serotonin 5-HT1B/D, and sigma-1 receptors. Volitional inhibition of the PAG is mediated by acetylcholine and GABA balance at this location.10

When to screen for PBA

Ask the right question. PBA as a disease state likely has been widely under-reported, under-recognized, and misdiagnosed (typically, as a primary mood disorder).9 Three factors underscore this problem:

- Patients do not specifically report symptoms of affective disturbance (perhaps because they lack a vocabulary to separate concepts of mood and affect)

- Physicians do not ask patients about separations of mood and affect

- Perhaps most importantly, PBA lacks a general awareness and understanding.

Co-occurring mood disorders also may thwart PBA detection. One study of PBA in Alzheimer’s dementia found that 53% of patients with symptoms consistent with PBA also had a distinct mood disorder.17 This suggests that a PBA-specific screening test is needed for accurate diagnosis.

A single question might best refine the likelihood that a patient has PBA: “Do you ever cry for no reason?” In primary psychiatric illness, crying typically is associated with a specific trigger (eg, depressed mood, despair, anxiety). A patient’s inability to identify a trigger for crying suggests the pathological separation of mood and affect—the core of PBA, and worthy of further investigation.