What’s the next best step in managing Mr. J’s care?

a) adjust his medication

b) eliminate a mediation

c) order further testing

The author’s observations

To determine if Mr. J’s new-onset symptoms might be related to the progression of his psychiatric illness, the haloperidol dosage was increased to 20 mg/d; however, we saw no positive response to this change. His tardive dyskinesia symptoms (bruxism and other oral buccal movements) worsened. Haloperidol was reduced to 10 mg/d.

Trihexyphenidyl then was suspected to contribute to Mr. J’s confusion. Unfortunately, lowering the dosage of trihexyphenidyl to 1 mg/d, did not affect Mr. J’s current symptoms and exacerbated extrapyramidal symptoms.

The treatment team then questioned if porphyria—known as the “little imitator”—might be considered because of the variety of symptoms without an etiology, despite extensive testing. A 24-hour urine collection was ordered.

What is the correct method of collecting a urine sample for porphyrins?

a) collect a small sample and expose it to light before testing

b) collect a 24-hour sample with the sample kept in ambient temperature and light

c) collect a 24-hour sample with the sample kept on ice in a light-blocking container and frozen when sent to the laboratory

EVALUATION Diagnosis revealed

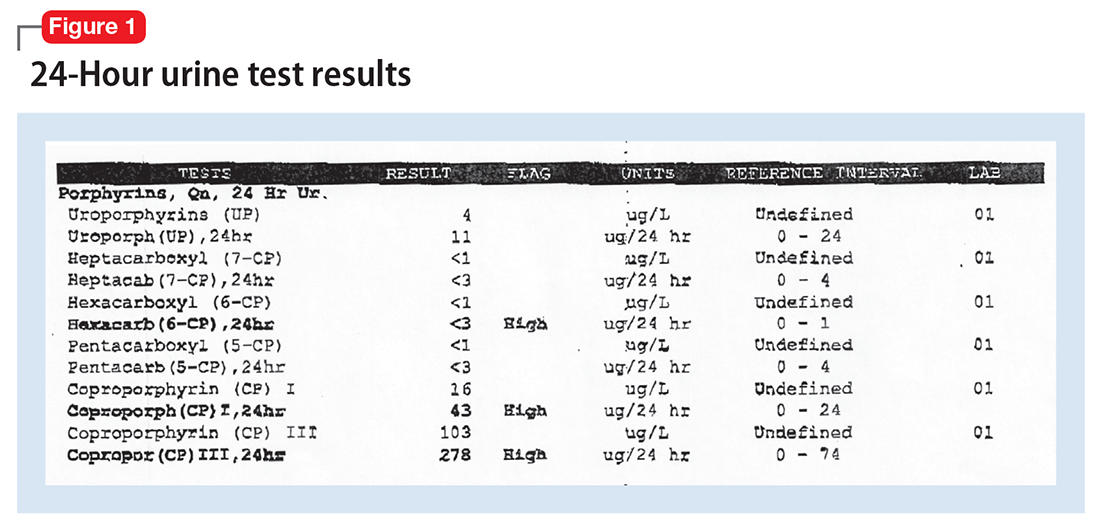

The 24-hour urine collection is obtained. However, it needed to be collected twice, because the first sample was not a full sample. Interestingly, the first sample, which is exposed to light and not kept on ice, turned dark in color. The second sample is obtained properly and sent to the laboratory. When the laboratory results are returned (Figure 1), Mr. J is diagnosed with hereditary coproporphyria (HCP).

The author’s observations

There are several types of porphyria, each associated with a different step in the chain of enzymes associated with synthesis of a heme molecule in the mitochondria. A defect in any single enzyme step will create a build up of porphyrins—a precursor to heme molecules—in erythrocytes or hepatic cells.

It is important to differentiate hepatic from erythropoietic porphyrias. The acute porphyrias (acute intermittent porphyria [AIP], HCP, and variegate porphyria generally are hepatic in origin with neuropsychiatric and neurovisceral symptoms. Cutaneous porphyrias originate in bone marrow and therefore are erythropoietic. However, there are exceptions such as porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), which is hepatic in origin but the manifestations mainly are cutaneous1 (Figure 2).2

Although acute porphyria originates in the liver, it is a neuropsychiatric illness. In these cases, excess porphyrins cannot cross the blood–brain barrier and are neurotoxic. Clinicians can look for abnormalities in the liver via liver function tests, but liver parenchyma is not damaged by these enzyme precursors. During an acute porphyic attack, patients could experience symptoms such as:

- muscle spasms (commonly abdominal, but can be any muscle group)

- confusion

- disorientation

- autonomic instability

- lightheadness

- disorientation

- diarrhea

- light sensitivity

- dermatologic conditions

- weakness (particularly peripheral weakness)

- hypesthesia

- allodynia

- severe nausea and vomiting

- emotional lability

- psychosis as well as general malaise.

The attack could result in death.

Mr. J had many differing symptoms and was evaluated by several specialty providers. He had a chronic dermatologic condition; he was confused, disoriented, and complained of nausea, weakness, orthostasis, and loose stools. With the variety of possible symptoms that patients such as Mr. J could experience, one can see why it would lead to many different providers being involved in the diagnosis. It is not uncommon for psychiatrists to be the last providers to care for such patients who could have been evaluated by hematology, cardiology, gastroenterology, dermatology, and/or neurology.