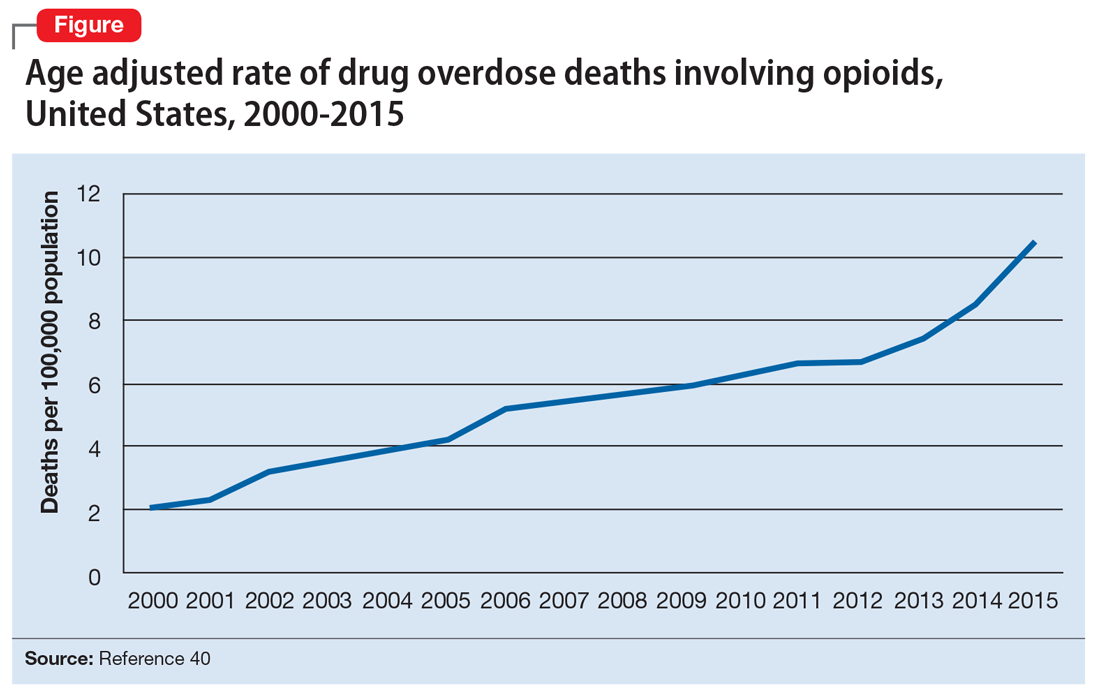

Opioid abuse and overdose are large and growing problems, and in recent years the numbers have been staggering. Overdose deaths related to opioids increased from 28,647 in 2014 to 33,091 in 2015 (Figure).1 More than 2 million individuals in the United States had opioid use disorder in 2015,2 and approximately 80% of them received no treatment,3 even though effective treatment could reduce the scope of abuse.4,5

Although psychiatrists typically are not the primary prescribers of opioid medications, they often treat psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic pain who take prescription opioids. A recent study found that, despite representing only 16% of the adult population, adults with mental health disorders receive more than one-half of all opioid prescriptions distributed each year in the United States.6 Therefore, psychiatrists must be aware of risk assessment strategies for patients receiving opioids.

In this article, we provide recommendations for managing individuals with opioid use disorder, including:

- how to identify risk factors for opioid use disorder and use screening tools

- how to evaluate a patient with suspected opioid use disorder and make the diagnosis

- how to treat a patient with opioid use disorder, including a review of approved pharmaceutical agents.

Risk factors for opioid abuse and overdose

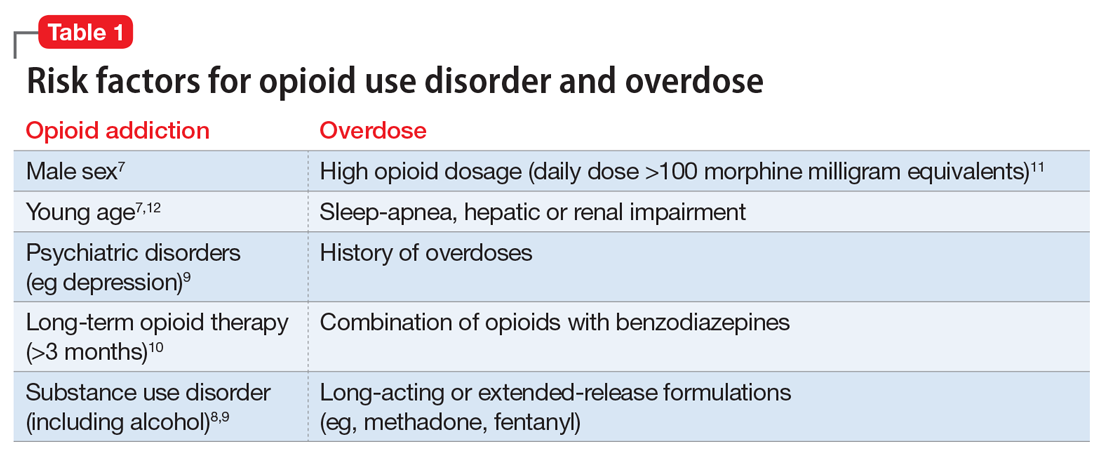

Patients with a history of mental health and/or substance use disorders or at least 3 months of prescribed opioid treatment are at risk for opioid abuse. Those taking a high daily dose of opioids or who have a history of overdose are at risk for overdose from opioid abuse (Table 1).7-12 Standardized tools, such as the Opioid Risk Tool, can be used to screen to assess risk for opioid abuse among individuals prescribed opioids for treatment of chronic pain.12 However, clinicians must be aware that even patients without characteristic risk factors can become dependent on opioids and/or be at risk for an accidental or intentional overdose. For example, opioid therapy following surgical procedures, even in patients who do not have a history of opioid use, increases risk of developing opioid use disorder.13

Evaluation and diagnosis

DSM-5 criteria define 3 degrees of opioid use disorder, depending on how many of the following traits a patient exhibits (mild, 2 to 3; moderate, 4 to 5; and severe, ≥6 )14:

- taking more than the initially intended quantities of opioids or for a longer period of time than intended

- continuous attempts to reduce or otherwise manage opioid use or desires to do so

- a great deal of time using, recovering from, or acquiring opioids

- reports of strong cravings to use opioids

- failing to meet personal objectives at home, work, or school

- continued opioid use even though it causes recurrent social problems

- reduction or elimination of activities the patient once considered important due to opioid use

- opioid use in situations where it is physically dangerous

- continued opioid use despite persistent psychological or physiologic problems despite knowing that continued use is causing or worsening those problems

- tolerance to opioids (not consequential for the diagnosis if the patient is taking opioids under appropriate medical supervision)

- withdrawal or use of opioids (or related substances) to prevent withdrawal (not consequential for the diagnosis if the patient is taking opioids under appropriate medical supervision).

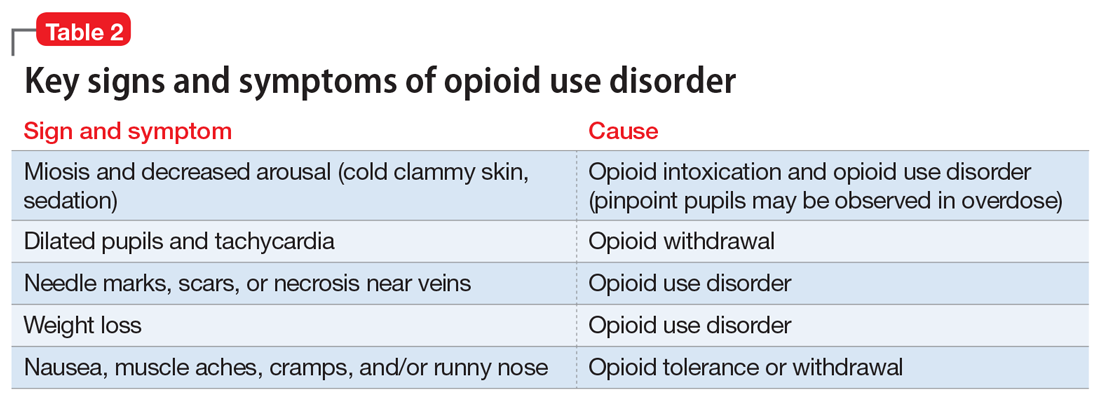

Clinicians should be vigilant for symptoms of opioid use or withdrawal, such as needle marks and weight loss, during the interview (Table 2). High-risk populations that require regular screening include individuals with a history of opioid use disorder, patients taking chronic pain medication, and psychiatric patients.15 During the interview, clinicians should take an nonjudgmental approach and avoid “shame and blame.”

Patients often will withhold information about drug use for various reasons.16 Therefore, collateral information from the patient’s family, close friends, or a referral source is important.

Standardized scales. Various standardized scales can be used to evaluate patients for opioid withdrawal and risk for substance use disorder. Scales for assessing opioid withdrawal include:

- Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale

- Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale.

Substance use disorder screening tools include:

- Drug Abuse Screen Test-10

- Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Drug Screening Tool.17

Examination findings. A brief physical examination is necessary to document key findings (Table 2). Patients should undergo a urine drug screen; gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy can confirm positive results. During the examination, clinicians should look for signs and symptoms of co-occurring substance use (eg, benzodiazepines, marijuana, alcohol, cocaine) or mental disorders (mood, anxiety, attention-deficit).18-21 Because nonprescription opioid use is associated with increased risk of suicide attempts and ideation,22 a suicide risk assessment is necessary.

Managing opioid use disorder

Detoxification is a 3-tiered approach that requires judicious prescription of medication, psychosocial support, and supervision to relieve opioid withdrawal symptoms. In both inpatient and outpatient settings, medications used for opioid detoxification include buprenorphine, clonidine, and methadone administered in doses tapered over 5 to 7 days. Appropriate detoxification increases treatment retention for continuing care.23,24

Buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone is the first-line option for outpatient and inpatient detoxification. Short-term detoxification schedules include starting doses between 4 and 16 mg/d, tapered over 5 to 7 days. Compared with methadone, buprenorphine has a lower risk of overdose25 and abuse potential and can be given in an office-based setting. Clonidine, 0.3 to 1.2 mg/d in divided doses, is an alternative to buprenorphine and can be used in inpatient settings.26

Clonidine is not as effective as buprenorphine for detoxification, but it may be used when buprenorphine is contraindicated. Clonidine may require adjuvant symptomatic treatment for insomnia (eg, trazodone, 100 mg at bedtime), anxiety (eg, hydroxyzine, 25 mg, twice a day), or diarrhea (loperamide, 2 mg/d). If a patient needs more structure and monitoring, he (she) should be referred for inpatient detoxification or to a methadone program.27