A neurologic exam shows impaired hearing bilaterally and impaired visual acuity. Even with glasses, both eyes have acuity only to finger counting. All other cranial nerves are normal, and Mr. B’s strength, sensation, and cerebellar function are all intact, without rigidity, numbness, or tingling. His gait is steady without a walker, with symmetric arm swing and slight dragging of his feet. His vitals are stable, with normal orthostatic pressures.

Other objective data include a score of 24/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, notable for deficits in visuospatial orientation, attention, and calculation, with language and copying limited by poor vision. Mr. B scores 16/22 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)-Blind (adapted version of MoCA), which is equivalent to a 22/30 on the MoCA, indicating some mild cognitive impairment; however, this modified test is still limited by his poor hearing. His serum and urine laboratory workup show no liver, kidney, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no sign of infection, negative urine drug screen, and normal B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. He undergoes a brain MRI, which shows chronic microvascular ischemic change, without mass lesions, infarction, or other pathology.

The authors’ observations

Given Mr. B’s presentation, we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder. He had no psychiatric history, with organized thought, a reactive affect, and no delusions, paranoia, or other psychotic symptoms, all pointing against psychosis. His brain MRI showed no malignancy or other lesions. He had no substance use history to suggest intoxication/withdrawal. His intact attention and orientation did not suggest delirium, and his serum and urine studies were all negative. Although his blaming Harry for knocking things out of his hands could suggest confabulation, Mr. B had no other signs of Korsakoff syndrome, such as ataxia, general confusion, or malnourishment.

We also considered early dementia. There was suspicion for Lewy body dementia given Mr. B’s prominent fluctuating visual hallucinations; however, he displayed no other signs of the disorder, such as parkinsonism, dysautonomia, or sensitivity to the antipsychotic (risperidone 1 mg nightly) started on admission. The presence of 1 core feature of Lewy body dementia—visual hallucinations—indicated a possible, but not probable, diagnosis. Additionally, Mr. B did not have the characteristic features of other types of dementia, such as the stepwise progression of vascular dementia, the behavioral disinhibition of frontotemporal dementia, or the insidious forgetfulness, confusion, language problems, or paranoia that may appear in Alzheimer’s disease. Remarkably, he had a relatively normal brain MRI for his age, given chronic microvascular ischemic changes, and cognitive testing that indicated only mild impairment further pointed against a dementia process.

Charles Bonnet syndrome

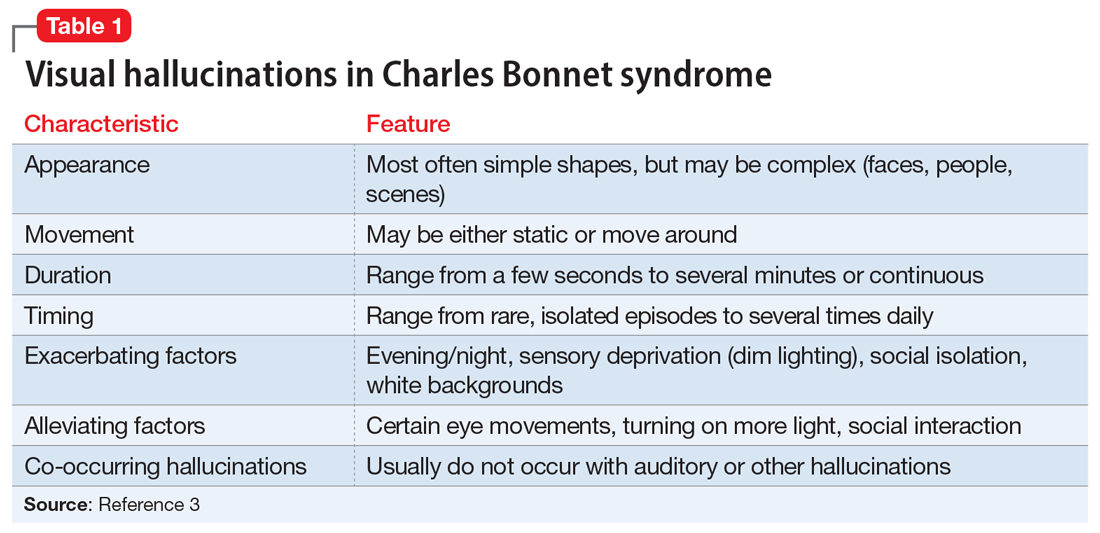

Based on Mr. B’s severe vision loss and history of ocular surgeries, we diagnosed him with CBS, described as visual hallucinations in the presence of impaired vision. Charles Bonnet syndrome has been observed in several disorders that affect vision, most commonly macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma, with an estimated prevalence of 11% to 39% in older patients with ocular disease.1,2 Visual hallucinations in CBS occur due to ocular disease, likely resulting from changes in afferent sensory input to visual cortical regions of the brain. Table 13 outlines the features of visual hallucinations in patients with CBS. The subsequent disinhibition and spontaneous firing of the visual association cortices leads to the “release hallucinations” of the syndrome.4 The disorder is thought to be significantly underdiagnosed—in a survey of patients with CBS, only 15% had reported their visual hallucinations to a physician.5

Continue to: Mr. B's symptoms...