Delirium is a common condition in hospitalized older patients. Often, a report of a “change in mental status” is the reason geriatric patients are sent to the emergency room for evaluation, although delirium also can develop after admission.

Delirium is a marker of underlying medical illness that needs careful workup and treatment. The condition can be iatrogenic, resulting from prescribed medication or a surgical procedure; most often, it is the consequence of multiple factors. Delirium can be expensive, because it increases hospital length of stay and overall costs—particularly if the patient is discharged to a nursing facility, not to home. Patients with delirium are at higher risk of death.

Delirium often goes unrecognized by physicians and nursing staff, and is not documented in medical records. Educating the medical staff on the identification and management of delirium is a key role for consulting psychiatrists.

CASE: Confused and agitated

Ms. T, a 93-year-old resident of an assisted living facility with a history of three

cerebral vascular accidents, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, multiple deep venous thromboses, blindness in her right eye, and deafness in her right ear without a hearing aid, is brought to the hospital after a syncopal episode lasting 10 minutes that was followed by slurred speech, confusion, and transient hypotension. Her dentist recently started her on azithromycin.

In the emergency room, Ms. T’s elevated blood pressure is managed with hydralazine and diltiazem. A CT scan of the head rules out hemorrhagic stroke. Complete blood count and tests of electrolytes, vitamin B12, and thyroid-stimulating hormone are within normal limits; urinalysis is negative for urinary tract infection.

Ms. T is noted to be in and out of sleep, with some confusion. She is maintained without oral food or fluids because of concerns about her ability to swallow. After 5 or 6 hours in the ER, Ms. T is transferred to a medical unit, where she becomes agitated and paranoid, with the delusion that her daughter is an impostor. She yells, is combative, and refuses medication.

Her confusion and behaviors become worse at night: She pulls out her IV line and telemetry leads. Blood pressure remains elevated, for which she receives additional doses of hydralazine.

For behavioral management, the medical team orders a one-time IM dose of haloperidol and starts her on risperidone, 0.5 mg every 4 hours as needed, which Ms. T refuses to take. She is incontinent and has foul-smelling urine.

Ms. T’s family is shocked at her condition; nursing staff is frustrated. With her worsening paranoia, delusions, and combative behaviors towards the nursing staff, psychiatry is consulted.

How to recognize and diagnose

The Box lists DSM-5 criteria for delirium.1 The key feature is a disturbance in attention—what was referred to in DSM-IV-TR as “disturbance in consciousness.” That finding contrasts with what is seen in dementia, with its hallmark memory impairment and chronic deterioration.

In a hospital setting, the question is often asked: Does this patient have dementia or delirium? In many cases, the answer is both, because preexisting cognitive impairment is an important risk factor for delirium.

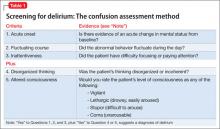

In addition to the standard clinical interview, several screening instruments or delirium rating scales have been developed. The most commonly used (Table 1) is the Confusion Assessment Method developed by Inouye and colleagues.2

Subtypes of delirium have been described, largely based on motor activity. Patients can present as hyperactive, hypoactive, mixed, or neither.3 Psychiatrists are more likely to be consulted regarding patients with hyperactive delirium, because they are the ones who scream, pull out their IV line, hallucinate, and are delusional, insisting they “have to go home”—such as the patient described in the case above.

Patients with hypoactive delirium often, on the other hand, are difficult to recognize; they present with lethargy, drowsiness, apathy, and confusion. They become withdrawn and answer slowly4; often, psychiatry is consulted to assess them for depression.

Delirium can be difficult to diagnose in patients with underlying dementia, who are not able to provide information. In such cases, obtaining collateral information from a family member or primary caretaker is crucial. Knowing the patient’s baseline helps to determine whether there has been an acute change in mental status.

CASE CONTINUED: Acute mental status changes

Ms. T’s daughter reports that her mother has not been in this condition before. At baseline, Ms. T has had memory problems but no paranoia, delusions, or agitated behaviors. Her daughter also reports that Ms. T has visual and hearing impairments and is not wearing her hearing aid.

The acute change in mental status and the perceptual disturbances indicate that Ms. T has delirium, not dementia.