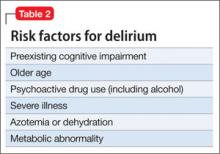

Who is likely to develop delirium?

Risk factors for delirium (Table 2) include preexisting cognitive impairment, older age, vision and hearing impairment, use of psychoactive drugs, severe illness, azotemia and dehydration, a metabolic abnormality, and infection. Male sex also seems to be a risk factor, perhaps because men are more likely to abuse alcohol before admission.

Many patients become delirious after starting a new medication. An experienced geriatrician teaches that the main causes of delirium are “drugs, drugs, drugs, infections, and everything else” (Kenneth Rockwood, MD, personal communication, 2012). At admission, urinary tract infection and pneumonia are common causes of delirium, especially in geriatric patients.

What is the clinical course?

The clinical course varies widely. Delirium often is the reason that a patient is brought to the hospital, presenting with the condition at admission or early in hospitalization. The highest incidence among surgical patients appears to be on the third postoperative day—in some cases because of alcohol or drug withdrawal.

As noted in the DSM-5 criteria, delirium often comes on acutely, over hours or days. Symptoms can persist for weeks after initial onset of episodes of delirium.5 Symptoms fluctuate over the course of the day; at times, they can be missed if a provider sees the patient only while she (he) is clearer and doesn’t review nursing notes from other shifts.

How does delirium affect outcome?

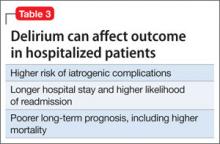

Delirium has been shown to be associated with prolonged hospital stay (21 days, compared with 11 days in the absence of delirium), functional decline during hospitalization, and increased admission to long-term care (36% compared with 13%).6 In a study by O’Keefe and Lavan,6 delirious patients were more likely to sustain falls and to develop urinary incontinence, pressure sores, and other complications during hospitalization.

Older patients with delirium superimposed on dementia had a more than twofold increased risk of mortality compared with patients with dementia alone or with neither dementia nor delirium.7 Rockwood found that an episode of delirium was associated with a much higher rate of subsequent dementia.8

Think of an acute medical illness as a “stress test” for the brain, such that, if the patient develops delirium, it suggests an underlying brain disease that was not evident before the acute episode. After hip fracture, for example, delirium was independently associated with poor functional recovery at 1 month9 and at 2 years.10

Older patients admitted to a skilled nursing facility with delirium are more likely to experience one or more complications (73% compared with 41%).11 In the study by Marcantonio and colleagues, patients with delirium were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized again within 30 days (30% and 13%), and less than half as likely to be discharged to the community (30% and 73%). Table 3 summarizes the impact of delirium on outcomes.

Appropriate management steps

Identifying and treating underlying medical illness is the definitive treatment for delirium; in a geriatric patient with multiple medical comorbidities the pathogenesis often is multifactorial or a definitive precipitant cannot always be identified.12

Managing a patient with delirium includes both non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions, which should be considered first-line, and pharmacotherapeutic interventions. Non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions include, but are not limited to:

• support and close observation by nursing staff

• placing a clock or calendar in the room

• frequent reorientation and reminders

• placing familiar possessions in the room

• putting the patient in an isolated room with a window

• regulating the sleep-wake cycle.4

Pharmacotherapeutic intervention in delirium should be used for behavioral symptoms, but only for the minimum duration necessary4 and preferably oral or IV. No drugs are FDA-approved for delirium, which means that use of any agent is off-label.13

Antipsychotics are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for delirium in most settings. The use of antipsychotics relates to the dopamine excess-acetylcholine deficiency hypothesis of delirium pathophysiology.12 Haloperidol remains the first-line agent because it is available in multiple dosages and can be given by various routes. IV haloperidol appears to carry less risk of extrapyramidal symptoms than oral haloperidol does but, as with all antipsychotics, its use warrants monitoring for QTc prolongation.12

Studies have not shown that atypical antipsychotics are superior to typical antipsychotics for delirium. Multiple studies have shown that atypicals are as efficacious as haloperidol.

Benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice for delirium caused by alcohol withdrawal. A Cochrane review found no evidence that benzodiazepines were helpful in treating delirium unrelated to alcohol withdrawal.14 In some studies, benzodiazepines were associated with an increased risk of delirium, especially in patients in the intensive care unit.15