Substances use during adolescence is common in the United States. Data from the 2014 Monitoring the Future Survey estimated that among 12th graders, 60.2% used alcohol, 35.1% used marijuana, and 13.9% used a prescription drug for nonmedical use within the previous year.1 An estimated 11.4% of adolescents meet DSM-IV threshold criteria for a substance use disorder (SUD).2 Substance use in adolescents often co-occurs with psychological distress and psychiatric illness. Adolescents with a psychiatric disorder are at increased risk for developing a SUD; conversely, high rates of psychiatric illness are seen in adolescents with a SUD.3,4 In one study, 82% of adolescents hospitalized for SUD treatment were found to have a co-occurring axis I disorder.5 Furthermore, co-occurring psychiatric illness and SUD complicates treatment course and prognosis. Adolescents with co-occurring psychiatric illness and SUD often benefit from an integrated, multimodal treatment approach that includes psychotherapy, pharmacologic interventions, family involvement, and collaboration with community supports.

In this article, we focus on pharmacologic management of non-nicotinic SUDs in adolescents, with an emphasis on those with comorbid psychiatric illness.

Screening and assessment of substance use

It is important to counsel children with a psychiatric illness and their parents about the increased risk for SUD before a patient transitions to adolescence. Discussions about substance abuse should begin during the 5th grade because data suggests that adolescent substance use often starts in middle school (6th to 9th grade). Clinicians should routinely screen adolescent patients for substance use. Nonproprietary screening tools available through the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse are listed in Table 1.6-8 The Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) is a newer tool that has been shown to be highly effective in identifying adolescents at risk for substance abuse and differentiating severity of illness.8 The S2BI includes screening questions that assess for use of 8 substances in the past year.

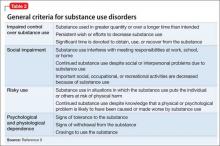

Adolescents with psychiatric illness who are identified to be at risk for problems associated with substance use should be evaluated further for the presence or absence of a SUD. The number of criteria a patient endorses over the past year (Table 29) is used to assess SUD severity—mild, moderate, or severe. Additional considerations include substance use patterns such as type, site, quantity, frequency, context, and combinations of substances.

It is important to be curious and nonjudgmental when evaluating substance use patterns with adolescents to obtain a comprehensive assessment. Teenagers often are creative and inventive in their efforts to maximize intoxication, which can put them at risk for complications associated with acute intoxication. Rapidly evolving methods of ingesting highly concentrated forms of tetrahydrocannabinol (“wax,” “dabs”) are an example of use patterns that are ahead of what is reported in the literature.

Any substance use in an adolescent with a psychiatric illness is of concern and should be monitored closely because of the potential impact of substance use on the co-occurring psychiatric illness and possible interactions between the abused substance and prescribed medication.

Treatment interventions

Although this review will focus on pharmacotherapy, individual, group, and family psychotherapies are a critical part of a treatment plan for adolescents with comorbid psychiatric illness and SUD (Table 3). Collaboration with community supports, including school and legal officials, can help reinforce contingencies and assist with connecting a teen with positive prosocial activities. Involvement with mutual help organizations, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, can facilitate adolescent engagement with a positive sober network.10

Pharmacologic strategies for treating co-occurring psychiatric illness and SUD include medication to:

• decrease substance use and promote abstinence

• alleviate withdrawal symptoms (medication to treat withdrawal symptoms and agonist treatments)

• block the effect of substance use (antagonist agents)

• decrease likelihood of substance use with aversive agents

• target comorbid psychiatric illness.

Medication to decrease substance use and promote abstinence. One strategy is to target cravings and urges to use substances with medication. Naltrexone is an opiate antagonist FDA-approved for treating alcohol and opioid use disorders in adults and is available as a daily oral medication and a monthly injectable depot preparation (extended-release naltrexone). Two small open-label studies showed decreased alcohol use with naltrexone treatment in adolescents with alcohol use disorder.11,12 In a randomized double-blind placebo controlled (RCT) crossover study of 22 adolescent problem drinkers, naltrexone, 50 mg/d, reduced the likelihood of drinking and heavy drinking (P ≤ .03).13 Acamprosate, another anti-craving medication FDA-approved for treating alcohol use disorder in adults, has no data on the safety or efficacy for adolescent alcohol use disorder.

There is limited research on agents that decrease use and promote abstinence from non-nicotinic substances other than alcohol. There is one pilot RCT that evaluated N-acetylcysteine (NAC)—an over-the-counter supplement that modulates the glutamate system—for treating adolescent Cannabis dependence. Treatment with NAC, 2,400 mg/d, was well tolerated and had twice the odds of increasing negative urine cannabinoid tests during treatment than placebo.14 Although NAC treatment was associated with decreased Cannabis use, it did not significantly decrease cravings compared with placebo.15