Pharmacotherapy to treat co-occurring psychiatric illness

Continued treatment of a psychiatric illness that co-occurs with SUD is important. As we recommended, consider psychosocial treatments for both the SUD and comorbid psychopathology. Several single-site RCTs have evaluated the efficacy of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine and sertraline for depressive disorders in adolescents with a co-occurring SUD.24-28 Most studies have shown improvement in depressive symptoms and substance use in medication and placebo groups.24,25,27,28 However, treatment with fluoxetine, 20 mg/d, or sertraline, 100 mg/d, when compared with placebo was associated with improved depressive symptoms in 1 of 3 studies and had no significant difference in SUD outcome. The authors of these studies believe that the general improvement in depression and the SUD was related to use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and/or motivational enhancement therapy.24,25,27,28

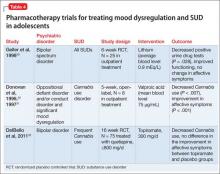

Research on the use of mood stabilizers for adolescents with mood dysregulation and a SUD is limited but has suggested benefit associated with pharmacotherapy (Table 4).29-32 Two RCTs and 1 open-label study demonstrated reductions in substance use with mood stabilizer treatment in adolescents with co-occurring SUD and mood dysregulation.29-32 The effect of pharmacotherapy on mood dysregulation ratings are less clear because there was no change in severity of affective symptoms observed in a small RCT of lithium (average blood level 0.9 mEq/L)29; and improvement in affective symptoms was noted in topiramate (300 mg/d) and placebo groups when both groups were treated with concurrent quetiapine.32 Because of the high risk of SUD and severe morbidity in juvenile bipolar disorder and severe mood dysregulation,33 larger RCTs are warranted.

Several studies have evaluated the impact of stimulant and nonstimulant treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adolescents with a co-occurring SUD.34-39 The largest and only multisite study evaluated the efficacy of osmotic (extended) release methylphenidate (OROS-MPH) vs placebo for adolescents who also were receiving CBT for SUD.36 In this 16-week RCT, the OROS-MPH and placebo groups showed improvement in self-reported ADHD symptoms with no difference between groups. Parent report of ADHD symptoms did indicate a greater reduction in symptoms in the OROS-MPH group compared with placebo. Both groups had a decrease in self-reported days of substance use over the past month with no differences between groups. Pharmacotherapy trials for ADHD that have included psychotherapy highlight the effectiveness of CBT for SUD and co-occurring psychiatric illness.36,39,40

Although conduct disorder and anxiety disorders commonly co-occur with SUD, there has been less research evaluating the impact of pharmacotherapy on treating these disorders. Riggs et al25,34,35,41 evaluated the impact of pharmacotherapy targeted to co-occurring ADHD and major depressive disorder in the context of conduct disorder and SUD. When evaluated in an outpatient setting, the presence of a treatment intervention to address the co-occurring SUD was an important component that led to a reduction in conduct symptoms.25,35 There have been no comprehensive studies on the impact of pharmacotherapy for treating anxiety and SUD in adolescents.

Recommendations for clinical management

Although more research is needed to evaluate the role of pharmacotherapy for adolescents with co-occurring psychiatric illness and a SUD, recommended practice is to continue pharmacotherapy and closely monitor response to treatment when at-risk substance use begins in patients with co-occurring psychiatric illness. In adolescents with a threshold SUD, continue pharmacotherapy for unstable mood disorders with first-line choices of SSRIs for unipolar depression and second-generation antipsychotics for bipolar spectrum illness. Suggested conservative pharmacological interventions for anxiety disorders include SSRIs and buspirone, which have been shown to be effective for treating anxiety in children and adolescents.42,43 For patients with comorbid ADHD and SUD, if possible, it is recommended to first stabilize substance use (low-level use or abstinence) and consider treating ADHD immediately thereafter with a nonstimulant such as atomoxetine, which has data on efficacy and safety in context to substance use; and/or an α-agonist or an extended-release stimulant. Because of the potential for misuse and toxicity associated with concurrent substance use, benzodiazepines should be considered a last treatment of choice for adolescents with anxiety disorders and a SUD. Similarly, the use of immediate-release stimulants should be avoided in patients with ADHD and a SUD. When prescribing medications that could be misused or toxic when combined with a substance, it is important to evaluate the risk and benefit of continued use of a particular medication and consider prescribing lower quantities to decrease risk for misuse (1- to 2-week supply). Adolescents often are reluctant to engage in SUD treatment and one strategy to consider is to make continued prescription of any medication contingent on engaging in SUD treatment. Enlist parents in helping to monitor, store, and administer their child’s medication to improve adherence and decrease the potential for misuse, diversion, and complications associated with substance intoxication.