As mentioned earlier, Don Grafton was the chief (and for a long time only) engineer at Arthrex. As he had no medical experience, I invited him to come to San Antonio to observe surgery. During Don’s many visits, I showed him pathology in the operating room and pointed out what I could do with the instruments I had and what I could not do. Then in the evening we went to my house and brainstormed how to perform the “missing” surgical manipulations, how to improve manipulations that were suboptimal, and how to optimize final surgical constructs.

Passing suture through tendon was an early challenge. One must remember that, in the early 1990s, it was not possible for machinists to fabricate complex shapes. Therefore, straight tubular retrograde suture passers were the logical first option. We initially developed spring-loaded retrograde hook retrievers (Figure 1) and then curved suture hooks with shuttling wires (Lasso). To me, the most unappealing feature of retrograde suture passage was the oblique angle of approach through the tendon, which caused a length–tension mismatch between the upper fibers and the lower fibers of the muscle–tendon unit. We recognized we could eliminate the mismatch if we passed the suture antegrade, such that it would pass perpendicular to the tendon fibers. These insights and efforts culminated in development of the Viper suture passer and then the FastPass Scorpion suture passer, which has a spring-loaded trapdoor on the upper jaw for ergonomic self-retrieving of the suture once it is passed through the tendon.

To develop a knot pusher that optimized knot tying (yielding the highest knot security and the tightest loop security), we used prototype instruments to tie and test literally thousands of knots in the laboratory. We were thus able to verify that the Surgeon’s Sixth Finger Knot Pusher (Arthrex) reproducibly tied optimized knots8,9 and also optimized knot fixation and bone fixation. However, our suture was not yet optimized and was prone to breakage, and our suture–tendon interface was not yet optimized. Clearly, improvement was needed in 2 more areas.

Don came up with the idea for a virtually unbreakable suture and developed that idea into FiberWire.10 Shortly thereafter, I contributed the idea and design for FiberTape, which dramatically enhanced suture pullout strength and footprint compression.

Anchor designs improved rapidly and dramatically. We made the second-generation BioCorkscrew fully threaded, which virtually eliminated anchor failure, even in soft bone.

Optimization of the suture–tendon interface took a giant step forward when Park and colleagues11,12 introduced linked double-row rotator cuff repair. Much as with a Chinese finger trap, the harder you pull, the stronger it becomes, with yield load approaching ultimate load.

At this point, it seemed we had optimized virtually every segment of the rotator cuff repair construct. Each component was just about as good as it could be. Or was it?

The Accidental Quest for Knotless Fixation

In November 1998, I made my first trip to China as a guest speaker at the Congress of the Hong Kong Orthopaedic Association. My first view of the magnificent Hong Kong skyline across Victoria Harbour was truly breathtaking. As I admired the gleaming glass towers and the concrete canyons of the city, I had no idea that the very next day these modern skyscrapers would reveal an ancient secret that would change my approach to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.

The day after my arrival, Dr. James Lam took me to lunch. As we approached the restaurant, he pointed across the street to a tall building that was being renovated and had scaffolding supporting workers alongside the first 9 stories of the exterior wall. Dr. Lam said that, after lunch, he would take me to the construction site for a closer look at the scaffolding.

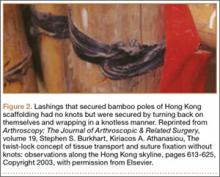

After lunch, we walked to the base of the scaffolding. Dr. Lam told me it was constructed entirely of bamboo poles held together with lashings but no knots (Figure 2). Lashings were secured by turning them back on themselves and wrapping them in an entirely knotless manner.13 I found it incredible that this knotless fixation was so secure that it could support the weight of workers many stories above the ground. I resolved to determine how this fixation method worked and see if the same mechanism might help us achieve reliable knotless fixation in surgery.

When I returned home, I broke out my college engineering books and reacquainted myself with the concept of cable friction. As has happened so often in the past, however, it took a practical lesson from the ranch to truly illustrate for me how cable friction works.