Serum studies, including C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and a complete blood count, were within normal limits. A CT-guided core needle biopsy and aspiration of the right SI joint revealed no infection; pathology was nondiagnostic. Anesthetic injection of the hip joint resulted in no relief. As this man was severely functionally limited and had exhausted all medical and radiation treatment options, a collaborative decision was made to proceed with surgical management. Surgical options included spinopelvic fusion unilaterally or bilaterally, hip arthroplasty, or sacropelvic resection with or without reconstruction. The patient opted for intralesional surgery and spinopelvic fusion in place of more radical options.

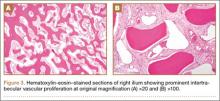

Thirty-seven months after his initial presentation, he underwent posterior spinal fusion L5 to S1, SI fusion, and anterior locking plate fixation of the pubic symphysis, as seen in Figure 2. Pathology from surgical specimens, seen at original magnification ×20 and ×100 in Figures 3A and 3B, respectively, showed prominent vascular proliferation in the right ilium, with reactive bone changes in the left ilium and right sacrum. A lytic lesion showed fibrous tissue with an embedded fragment of necrotic bone.

Six weeks after surgery, the patient had substantial improvement in his pain and was partially weight-bearing. He was able to ambulate with crutches and returned to work. The patient’s overall clinical status continued to improve throughout the postoperative course. He developed low back pain 7 months after surgery and was found to have a sacrococcygeal abscess and coccygeal fracture anterior to the sacrum. He underwent irrigation and débridement of the abscess and distal coccygectomy and was treated with 6 weeks of intravenous cefazolin and long-term suppression with levofloxacin and rifampin for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus hardware infection and osteomyelitis. The patient’s clinical course subsequently improved. At latest follow-up 16 months after the index operation, pain was reported as manageable and mostly an annoyance. He was prescribed up to 40 mg of oxycodone daily for pain. The patient returned to work, ambulates with a cane (no other assistive devices), and reports being able to get around without any difficulty.

Discussion

Gorham-Stout disease is an exceedingly rare condition resulting in spontaneous osteolysis. Approximately 200 cases have been reported with no apparent gender, race, or familial predilection or systemic symptoms differentiating it from other etiologies of idiopathic osteolysis.6 These patients often seek medical attention after sustaining a pathologic fracture,6 when a broad differential diagnosis narrows to GSD only after biopsy excludes other possibilities and demonstrates characteristic angiomatosis without malignant features.2,4,6,8,10 Gorham-Stout disease appears more frequently at particular sites within the skeleton, and pelvic involvement is common—more than 20% of cases in 1 review.5,10 Limitations in the patient’s ability to ambulate invariably result from osteolysis of the pelvis, which is concerning considering the young age at which GSD typically presents. A variety of treatment modalities have been described for pelvic GSD, but surgery has been undertaken in relatively few cases.5

The diagnosis is one of exclusion after considering the clinical context and radiologic and pathologic findings. In this case, a pathologic fracture was discovered with osteolytic lesions throughout the hemipelvis. Biopsy excluded malignancy and demonstrated the key hemangiomatous vascular proliferation with thin-walled vessels that is classic for GSD. While our patient initially appeared to have 2 sites of disease, the surgical specimen revealed a primary site of vascular proliferation in the right ilium from which 2 apparent foci had spread, consistent with the typical monocentric presentation of GSD.11 A broad differential diagnosis must be considered at initial presentation, including osteomyelitis, metastatic disease, multiple myeloma, and primary bone sarcoma. Upon identifying a primary osteolytic process, several considerations besides GSD remain, such as Hajdu-Cheney syndrome, Winchester syndrome, multicentric osteolysis with nephropathy, familial osteolysis, Farber disease, and neurogenic osteolysis; most of these etiologies involve familial predispositions and/or systemic symptoms.

Treatment options for GSD include supportive care, medical therapy, radiation, and surgery. For pelvic GSD, numerous reports have demonstrated good outcomes with supportive management, since osteolysis often spontaneously arrests.8,9,12 Others have had success with medical treatments in attempts to halt bone resorption.6,13-15 Bisphosphonates are the cornerstone of medical therapy in GSD, as they appear to halt further osteoclastic bone breakdown. The levels of VEGF have been shown to be elevated in GSD,13 likely consistent with the vascular proliferation evident on pathology, and therapies such as bevacizumab and interferon α-2b have been used to target osteolysis via this pathway with good outcome.13,14,16 External beam-radiation therapy has been shown to prevent local progression of osteolysis in up to 80% of cases.4 However, even with arrest of bone resorption, damage to affected bone may have progressed to the point of significant functional limitation. This may be especially true in the pelvis.