Gorham-Stout disease (GSD) is a rare condition characterized by spontaneous idiopathic resorption of bone with lymphovascular proliferation and an absence of malignant features. It was originally described by Jackson1 in an 1838 report of a 36-year-old man whose “arm bone, between the shoulder and elbow” had completely vanished after 2 fractures. The disease was defined and its pathology characterized by Gorham and Stout2 in 1955 in a series of 24 patients. Despite about 200 reported cases in the literature,3 its etiology remains unclear. Any bone in the skeleton may be affected by GSD, although there is a predilection for the skull, humerus, clavicle, ribs, pelvis, and femur.4-6 It commonly manifests within the first 3 decades of life, but case reports range from as early as 2 months of age to the eighth decade.5,7

Gorham-Stout disease is a diagnosis of exclusion that requires careful consideration of the clinical context, radiographic findings, and histopathology. Typical histopathologic findings include benign lymphatic or vascular proliferation, involution of adipose tissue within the bone marrow, and thinning of bony trabeculae.6 Fibrous tissue may replace vascular tissue after the initial vasoproliferative, osteolytic phase.6 Some authors describe the disease as having 2 phases, the first with massive osteolysis followed by relative dormancy and the second without progression or re-ossification.8,9 Treatment remains controversial and is guided by management of the disease’s complications. Options range from careful observation and supportive management to aggressive surgical resection and reconstruction, with positive outcomes reported using many different modalities.10 Most treatment successes, however, hinge on halting bony resorption using medical and radiation therapy. Surgery is usually reserved as a salvage option for patients who have failed medical modalities and have residual symptoms or functional limitations.6

This case report describes the successful surgical management of a patient with pelvic GSD who had progressive pain and functional limitation despite exhaustive medical and radiation therapy. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A healthy 27-year-old man sought medical attention after a fall while mowing his lawn that resulted in difficulty ambulating. Radiographic studies showed discontinuous lytic lesions in the right periacetabular region and the right sacroiliac (SI) joint. Biopsy at an outside institution revealed an infiltration of thin-walled branching vascular channels involving intertrabecular marrow spaces and periosteal connective tissue. The vessels were devoid of a muscular coat and lined by flattened epithelium; these features were seen as consistent with GSD.

The patient was managed medically at the outside institution for approximately 2 years, with regimens consisting of zoledronate, denosumab, sorafenib, vincristine, sirolimus, and bevacizumab. Because there is no standard chemotherapy protocol for GSD, this broad regimen was likely an attempt by treating physicians to control disease progression before considering radiation or surgery. Zoledronate, a bisphosphonate, and denosumab, a monoclonal antibody against the receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand (RANKL), both inhibit bone resorption, making them logical choices in treating an osteolytic disease. Sorafenib, vincristine, sirolimus, and bevacizumab may be of clinical benefit in GSD via inhibition of vascular proliferation, which is a key histologic feature in GSD. Sorafenib inhibits the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor, vincristine and sirolimus inhibit VEGF production, and bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF.

The patient’s disease continued to involve more of his right hemipelvis despite this extensive regimen of chemotherapy, and he experienced significant functional decline about 2 years after initial presentation, when he was no longer able to ambulate unassisted. Radiation therapy to the pelvis was attempted at the outside institution (6/15 MV photons, 5040 cGy, 28 fractions) without improvement. Three years after his initial injury, he presented to our clinic.

Now age 30 years, the patient ambulated only with crutches and endorsed minimal improvement in his pain over 3 years of treatment. Physical examination of the patient revealed that he was a tall, thin man in visible discomfort. Sensation was intact to light touch in the bilateral L1 to S1 nerve distributions. There was marked weakness of the right lower extremity, and his examination was limited by pain. He could not perform a straight leg raise on the right side. Right quadriceps strength was 4/5, and right hamstrings strength was 3/5. There was no weakness in the left leg. Reflexes were normal and symmetric bilaterally at the patellar and gastrocnemius soleus tendons. Distal circulatory status in both extremities was normal, and there were no deformities of the skin.

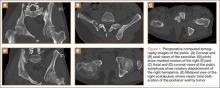

Figure 1 shows the patient’s computed tomography (CT) scan. Figures 1A and 1B reveal fragmentation of the posterior ilia and sacrum along both SI joints. Dislocation of the pubic symphysis is shown in Figures 1C and 1D, and discontinuous involvement of the ischium and posterior wall of the acetabulum is visible in Figure 1E.