At this time, the 2 semiautonomous systems in use for UKA employ different methods to safeguard against inadvertent bone preparation: one by providing haptic constraint beyond which movement of the bur is limited (Mako); the other by modulating the exposure or speed of the handheld robotic bur (Navio) (Figure 3).

Outcomes of RAS in UKA

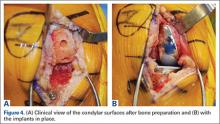

Compared to conventional UKA, robotic assistance has consistently demonstrated improved surgical accuracy, even through minimally invasive incisions (Figures 4, 5).6,20-28 Several studies have found substantial reduction in variability and error of component positioning with use of semiautonomous robotic tools.6,21,25 In fact, precision appears to be comparable regardless of whether an image-free system or one requiring a preoperative CT scan is used (Table). Further, in addition to improving component and limb alignment, Plate and colleagues22 demonstrated that RAS-based UKA systems can help the surgeon precisely reproduce plans for soft-tissue balancing. The authors reported ligament balancing to be accurate up to .53 mm compared to the preoperative plan, with approximately 83% of cases balanced within 1 mm of the plan through a full range of flexion.22

When evaluating advanced and novel technologies, there is undoubtedly concern that there will be increased operative time and a substantial learning curve with those technologies. Karia and colleagues30 found that when inexperienced surgeons performed UKA on synthetic bone models using robotics, the mean compound rotational and translational errors were lower than when conventional techniques were used. Among those using conventional techniques, although surgical times improved during the learning period, positional inaccuracies persisted. On the other hand, robotic assistance enabled surgeons to achieve precision and accuracy when positioning UKA components irrespective of their learning experience.30 Another study, by Coon,31 similarly suggested a shorter learning curve and greater accuracy with RAS using the Mako system compared to conventional techniques. A prospective, multicenter, observational study evaluated the operative times of 11 surgeons during their initial clinical cases using Navio robotic technology for medial UKA after a period of training using cadaver knees and sawbones.41 The learning curve for total surgical time (tracker placement to implant trial phase) indicates that it takes 8 cases to achieve 95% of total learning and maintain a steady state surgical time.

Potential Disadvantages of RAS in UKA

RAS for UKA has several potential disadvantages that must be weighed against their potential benefits. One major barrier to broader use of RAS is the increased cost associated with the technologies.17,19,27,32 Capital and maintenance costs for these systems can be high, and those that require additional advanced imaging, such as CT scans, further challenge the return on investment.17,19,32 In a Markov analysis of one robotic system (Mako), Moschetti and colleagues17 found that if one assumes a system cost of $1.362 million, value can be attained due to slightly better outcomes despite being more expensive than traditional methods. Nonetheless, their analysis of the Mako system estimated that each robot-assisted UKA case cost $19,219, compared to $16,476 with traditional UKA, and was associated with an incremental cost of $47,180 per quality-adjusted life-year. Their analysis further demonstrated that the cost-effectiveness was very sensitive to case volume, with lower costs realized once volumes surpassed 94 cases per year. On the other hand, costs (and thus value) will also obviously vary depending on the capital costs, annual service charges, and avoidance of unnecessary preoperative scans.19 For instance, assuming a cost of $500,000 for the image-free Navio robotic system, return on investment is achievable within 25 cases annually, roughly one-quarter of the cases necessary with the image-based system.

Another disadvantage of RAS systems in UKA is the unique complications associated with their use. Both RAS and conventional UKA can be complicated by similar problems such as component loosening, polyethylene wear, progressive arthritis, infection, stiffness, instability, and thromboembolism. RAS systems, however, carry the additional risk of specific robot-related issues.19,27 Perhaps most notably, the pin tracts for the required optical tracking arrays can create a stress riser in the cortical bone,19,27,33,42 highlighting the importance of inserting these pins in metaphyseal, and not diaphyseal, bone. Soft tissue complications have been reported during bone preparation with autonomous systems in total knee and hip arthroplasty;37,38 however, the senior author (JHL) has not observed that in 1000 consecutive cases with either semiautonomous surgeon-driven robotic tool.19

Finally, systems that require a preoperative CT scan pose an increased radiation risk.40 Ponzio and Lonner40 recently reported that each preoperative CT scan for robotic-assisted knee arthroplasty (using a Mako protocol) is associated with a mean effective dose of radiation of 4.8 mSv, which is approximately equivalent to 48 chest radiographs.34 Further, in that study, at least 25% of patients had been subjected to multiple scans, with some being exposed to cumulative effective doses of up to 103 mSv. This risk should not be considered completely negligible given that 10 mSv may be associated with an increase in the possibility of fatal cancer, and an estimated 29,000 excess cancer cases in the United States annually are reportedly caused by CT scans.40,43,44 However, this increased radiation risk is not inherent to all RAS systems. Image-free systems, such as Navio, do not require CT scans and are thus not associated with this potential disadvantage.