Take-Home Points

- Patellofemoral osteotomies can provide excellent and reliable symptomatic relief for many patients with symptomatic isolated PFOA.

- PLPF of 1 cm to 1.5 cm of lateral bone can provide excellent pain relief in patients with isolated lateral facet arthritis and overhanging osteophytes without diffuse chondromalacia or hypermobility.

- At 5-year follow-up, >80% of partial lateral facetectomy patients have symptomatic relief.

- Tibial tubercle AMZ (Fulkerson procedure) can provide excellent results in patients with distal and lateral patella chondropathy.

- Avoidance of overmedialization, early range of motion, and limited weight-bearing can help avoid complications associated with tibial tubercle AMZ.

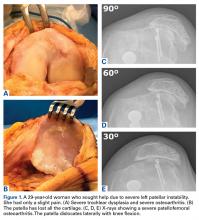

Isolated patellofemoral osteoarthritis (PFOA) is a relatively common disorder. Based on radiological evidence, its prevalence is 24% in women and 11% in men aged over 55 years.1 However, the presence of PFOA on radiographic images does not always correlate with clinical symptoms. PFOA is symptomatic in only 8% of women and 2% of men aged over 55 years,1 and a mismatch often occurs between the symptoms and radiological severity (Figures 1A-1E).

In young patients, PFOA occurs at the lateral facet of the patella in 89% of the cases.2 Patients with primarily lateral facet lesions can have excellent outcomes with osteotomy surgery.PFOA surgery may be considered when nonsurgical treatment is ineffective and pain becomes disabling. However, which surgical treatment for isolated PFOA is optimal remains controversial. The largest setback in weighing nonarthroplasty surgical options for isolated PFOA is that few studies have been published. Furthermore, published studies offer little scientific evidence; they include case series with few patients and retrospective analyses with limited follow-up and no control group for comparison.

This article focuses on osteotomies, which are described in only 15 articles found through PubMed. The small number is logical given that the prevalence of symptomatic isolated PFOA is low1 and that the majority of patients do not need surgical treatment. A complicating factor is that osteotomy is often associated with other surgical procedures, such as lateral retinaculum release. In descriptions of these cases, it is not clear if the outcome for PFOA is attributable to the osteotomy, is secondary to the associated procedure, or both.

Several alternatives to patellofemoral arthroplasty—partial lateral patellar facetectomy (PLPF), patella-thinning osteotomy (PTO), anteromedialization (AMZ), and sulcus-deepening trochleoplasty (SDT)—are available for the management of isolated PFOA. In this article, we analyze the value of each of these techniques in preserving the patellofemoral joint in the presence of PFOA. These techniques combine the US and European perspectives. The ultimate objective with these surgical techniques is to delay arthroplasty as long as possible.

Partial Lateral Patellar Facetectomy

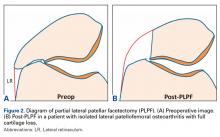

PLPF is a relatively simple and effective surgical treatment for isolated PFOA in active middle-aged to elderly patients who want to maintain their activity level.3-6 Using an oscillating saw to resect 1 cm to 1.5 cm of the lateral facet of the patella reduces lateral retinaculum tension and thereby decreases lateral patellofemoral contact pressures (Figures 2A, 2B).

PLPF is indicated in isolated lateral PFOA with full cartilage loss and lateral patellar osteophytes associated with localized lateral patellar tenderness, a negative passive patellar tilt test, excess lateral patellar tilt on radiographs, and normal patellofemoral tracking (tibial tubercle-trochlear groove [TT-TG] distance, <20 mm). The main contraindications are medial or diffuse patellar chondropathy and patellar hypermobility.PLPF improves pain and function over the long-term and delays the need for major surgery. Wetzels and Bellemans5 evaluated 155 consecutive patients (168 knees) with mean post-PLPF follow-up of 10.9 years. By final follow-up, 62 knees (36.9%) had failed and been revised to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) (60 knees), patellofemoral arthroplasty (1 knee), or total patellectomy (1 knee). Mean time to reoperation was 8 years. Kaplan-Meier survival rates with reoperation as the endpoint were 85% at 5 years, 67.2% at 10 years, and 46.7% at 20 years. At final follow-up, 79 (74.5%) of the 106 knees that had not been revised were rated good or fair, which accounts for 47% of the original group of 168 knees. The key finding is that the effects of PLPF lasted through the 10-year follow-up in half of the patients.5 Paulos and colleagues4 found 5 years of symptomatic relief in more than 80% of carefully selected patients who did not have significant (grade IV) arthritis in the medial or lateral knee compartments.

PLPF is a safe, low-cost, and relatively minor surgery with a low morbidity rate and fast recovery. Also, it does not close the door on other surgery and can easily be converted to TKA. Wetzels and Bellemans5 found that 36.9% of reoperations were TKAs, and López-Franco and colleagues3 found that 30% of knees required secondary TKA.