PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Normal gastrointestinal flora resist colonization and proliferation of C difficile; colonization of nontoxigenic strains appears to be protective against toxigenic strains.1 Alteration in the colonic bacterial environment, including the suppression of normal flora proliferation that can occur when a patient receives antibiotics or antineoplastic agents, is thought to allow the overgrowth of C difficile.2

Only C difficile strains that produce exotoxins (the enterotoxin toxin A, and the cytotoxin toxin B) are pathogenic. The organism produces a variety of adhesion proteins (with production accelerated by the presence of antibiotics, such as ampicillin and clindamycin), leading the toxins to bind to specific receptors in the intestinal mucosal cells. C difficile also produces proteases that trigger degradation of the intestinal extracellular matrix and disruption of epithelial cell signaling.16 The toxins activate proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-, and IL-8. The result is an intestinal inflammatory response that is clinically apparent in the form of diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis (PMC).20

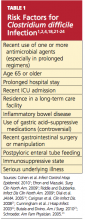

RISK FACTORS

Among several known risk factors for CDI (see Table 11,2,4,18,21-24), perhaps the most widely recognized is the use of nearly any antimicrobial agent. Previous administration of antibiotics has been documented in about 95% of inpatients with CDI. Broad-spectrum antibiotics with anti-anaerobic coverage appear to pose the greatest risk.1,4 These include clindamycin, along with cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and beta-lactams.1,13 Fluoroquinolone use has been implicated in the development of the NAP1 subtype of the disease.25 In patients who receive multiple antibiotics or prolonged courses, an even greater risk for CDI is incurred.4 Even single-dose administration of an antibiotic carries a CDI risk of about 1.5%.21

A prolonged hospital stay or residence in a long-term care facility increases the risk for CDI, as does advanced age.1 Patients 65 or older have a 20-fold higher risk for CDI than their younger counterparts.1,2 Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have an increased risk for CDI.23

It has been theorized that the use of gastric acid–suppressive medications can increase the risk for CDI to between 2.5 and 2.9 times that among persons who do not take these agents.18,22 Results from other trials have refuted this theory, however.13,26

Additional risk factors include ICU admission, recent gastrointestinal surgery or manipulation, immunosuppression, and serious underlying illnesses.24 Postpyloric enteral tube feeding has also been implicated as a risk factor; this route bypasses the stomach, where a very acidic environment ordinarily helps to kill the organism.4

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Watery diarrhea, occurring 10 to 15 times in a day, is the most common manifestation of CDI. It may present during administration of an antimicrobial agent or within a few days afterward; rarely, it can develop as long as two months after cessation of such treatment.2 In most studies, median onset of diarrhea is about two days.20 Descriptive characteristics of the stool, including odor and color, may vary. Diarrhea may be accompanied by lower abdominal pain, cramping, low-grade fever, and leukocytosis.

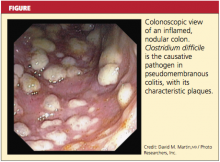

In some patients, particularly those taking narcotics, diarrhea may be absent. This manifestation may signal a more severe disease course, including the possibility of fulminant infection. Endoscopic evaluation of the colon may reveal the classic pseudomembranes (ie, adherent yellow plaques)2; see figure.

Stratifying Disease Severity

The severity of CDI-associated colitis increases as systemic symptoms worsen and the clinical picture deteriorates.4 In the 2010 SHEA-IDSA guidelines,1 CDI is stratified, both in the initial episode and the first recurrence, as mild-to-moderate, severe, or severe complicated. The following data may be used to appropriately stage disease severity in the initial episode:

• Mild-to-moderate disease is characterized by nonbloody diarrhea (fewer than 10 to 12 bowel movements per day), possibly accompanied by mild, crampy abdominal pain. Typically, affected patients do not exhibit significant systemic symptoms or marked abdominal tenderness. Leukocytosis is usually represented by fewer than 15,000 cells/L, and the serum creatinine level is less than 1.5 times the baseline level.1,2,5,8

• Severe disease, which should always be a consideration in older patients,1 includes profuse, watery diarrhea, significant abdominal pain and distension, fever, nausea and vomiting, and clinical volume depletion. Significant leukocytosis (≥ 15,000 cells/L) and serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 times baseline or leukopenia with possible bandemia may occur.1,27 Occult blood may be present, but frank blood is rare. A history of ICU admission alone increases the classification to severe due to the aforementioned poor outcomes associated with CDI in ICU patients.8,24

• Severe, complicated CDI may involve hypotension, shock, or a paralytic ileus1; a paradoxical decrease or absence of diarrhea may occur.2 At the severe end of the disease spectrum, toxic megacolon can develop and progress to colonic perforation.2,5,8,28 Hypoalbuminemia may be present due to the large protein losses in the course of the disease.28