Aggressive fluid and electrolyte replacement should be administered until diarrhea has been resolved (usually within three to six days). Patients may require vasoactive medications to support hemodynamics.2,5,14,24

Patients with mild disease can eat as they normally would. Those with severe disease, including those who may require surgery, fare best with bowel rest and possibly enteral nutrition.

Monitoring the patient for signs of improvement during the first 24 to 48 hours is an important component of management. The patient’s white blood cell count and temperature, the number and frequency of bowel movements, and the overall clinical picture should be evaluated daily. Patients who show improvement should complete the current regimen.

TREATMENT FAILURE AND RECURRENT CDI

If a patient’s condition does not improve or worsens at any point during therapy for CDI, a change to another antimicrobial agent is warranted. Also, surgical, gastroenterological, and/or infectious disease consult may be needed if no improvement is evident after five days of seemingly appropriate therapy.14,24

Recurrent CDI, which occurs at least once in 6% to 25% of treated patients, is most likely to occur 7 to 14 days after treatment completion.1,14 Seldom caused by resistant strains of C difficile, it is more likely to result from inadequate adherence to treatment, the presence of residual spores in the colon after treatment, or reinfection—although relapse is considered more common than reinfection.14,24 However, since a patient’s symptoms may have other causes, confirmation of recurrence should be sought through laboratory testing.

Recurrent illness is managed in the same way as successful initial therapy, based on the severity of disease; vancomycin is recommended for the first recurrence in a patient with a rising white blood cell count or serum creatinine level. Otherwise, metronidazole use may be considered.1

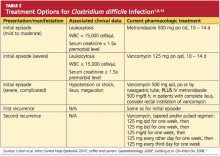

In patients who experience a second recurrence of confirmed CDI, a tapered or pulsed-dose regimen of oral vancomycin over a six-week period has been advocated1,8,14 (for details, see Table 2).

Results from small studies of patients with several recurrences of CDI suggest that oral rifaximin therapy can reduce subsequent recurrences if administered immediately after the conclusion of a course of vancomycin.1,41

PREVENTION OF C DIFFICILE INFECTION

Although “research gaps” exist regarding the optimal strategies to prevent CDI,1 decreased prescribing of nonessential antibiotics is key. Without the alteration in colonic flora caused by antimicrobial use, gut colonization cannot occur, and C difficile typically cannot proliferate.2

Preventing transmission of the pathogen is challenging in health care facilities, where C difficile spores have been cultured from staff members’ hands and from beds, floors, windowsills, and other areas; the spores can survive in hospital rooms for as long as 40 days after a patient with CDI has been discharged.24 Appropriate isolation precautions are essential, including single-patient–use equipment (eg, disposable rectal thermometers) and caregivers’ use of gowns, vinyl gloves, and cleaning agents that are effective against the spores, particularly bleach.1 Alcohol-based products are not effective against C difficile spores; diligent handwashing with soap or chlorhexidine is imperative to prevent the spread of CDI.1,2

CONCLUSION

Clinicians and patients alike face the clinical challenge of Clostridium difficile infection. Mild to moderate disease can be treated medically with excellent success rates. Severe disease carries a significant risk to life, and a multidisciplinary approach including early surgical consultation is warranted.

With early recognition and appropriate treatment, along with strict adherence to isolation policies, the health care community can help limit the spread of this insidious illness and its associated morbidity and mortality.

REFERENCES

1. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455.

2. Efron PA, Mazuski JE. Clostridium difficile colitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89(2):483-500.

3. Hall IC, O’Toole E. Intestinal flora in newborn infants with a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficilis. Am J Dis Child. 1935;49:390-402.

4. Riddle DJ, Dubberke ER. Clostridium difficile infection in the intensive care unit. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2009;23(3):727-743.

5. Sunenshine RH, McDonald LC. Clostridium difficile–associated disease: new challenges from an established pathogen. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006; 73(2):187-197.

6. Currie B. Improved testing methods are improving diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infections. Advance Administrators Laboratory. 2009;21:10. http://laboratory-manager.advance web.com/Article/PCR-for-C-diff.aspx. Accessed November 8, 2011.

7. Larson HE, Barclay FE, Honour P, Hill ID. Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile in infants. J Infect Dis. 1982;146(6):727-733.

8. Leffler DA, Lamont JT. Treatment of Clostridium difficile–associated disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(6):1899-1912.

9. Kelly CP, Lamont JT. Clostridium difficile: more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18): 1932-1940.