The Most Severe Manifestations

Fulminant CDI can occur in 3% to 8% of patients with CDI.27,29 Fulminant disease carries a mortality rate between 35% and 80%.23 The patient’s clinical picture may resemble that seen in severe disease, with the addition of an acute abdomen indicating peritonitis; lethargy, hypotension, oliguria (including renal failure), and/or tachycardia due to a severe systemic inflammatory response induced by toxin production from C difficile. Up to 20% of patients with fulminant C difficile do not have diarrhea due to reasons explained previously.2,5,23

Bacteremia occurs rarely in patients with CDI.1,30 Risk factors for this severe condition include failure of medical treatment, leukocytosis exceeding 16,000 cells/L, surgery in the previous 30 days, a history of IBD, and previous administration of IV immunoglobulin.23

DIAGNOSIS

According to recommendations from the SHEA-IDSA expert panel,1 only unformed stool from symptomatic patients should be tested for C difficile or its toxins. In spite of slow turnaround time, stool culture (followed by toxigenic culture to identify a toxigenic isolate) is currently considered standard testing for C difficile. Cell cytotoxin assay has 98% sensitivity and 99% specificity, but turnaround time is 24 to 48 hours,28 potentially delaying treatment for patients who test positive.

Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing for C difficile toxin A and toxin B yields results within hours but is not as sensitive as the cell cytotoxin assay.1 Because toxin testing lacks sensitivity, a two-step strategy has been proposed and is called an “interim recommendation” by the SHEA-IDSA guideline authors: EIA testing for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), an enzyme produced by C difficile; then, in patients with positive results, confirmation by cell cytotoxin assay or toxigenic culture.1,4,28 (EIA testing for GDH can be a rapid, inexpensive method for ruling out CDI.28)

Polymerase chain reaction testing, recently developed for the detection of pathogenic C difficile, is rapid, sensitive, and specific.1 However, this method has not yet gained wide acceptance due to its relatively high cost.6

Imaging Options

Endoscopic visualization confirming the presence of PMC is also considered diagnostic of CDI; although half of patients with CDI lack this finding on endoscopy, CDI is present in 95% of patients with confirmed PMC.1,28 Colonoscopy is advantageous over sigmoidoscopy because up to one-third of patients have only right-sided colonic involvement.28 To its disadvantage, endoscopy carries a risk for perforation (particularly in patients with fulminant disease), as well as the inherent risks of sedation required to perform the procedure.

Though not specific, CT can be used as an adjunct to the diagnosis; features such as colonic wall thickening, pericolic stranding, ascites, pneumatosis, and free air resulting from perforation may suggest CDI and help determine the extent of disease.4,20 The accordion sign (high-attenuation oral contrast in the colon lumen, alternating with low attenuation of inflamed mucosa) and the double halo sign (IV contrast having varying degrees of attenuation due to submucosal inflammation and hyperemia) have also been reported in patients with CDI and may indicate PMC or fulminant CDI.28

The small intestine is typically not involved in CDI except in the setting of ileus and the rare entity of C difficile enteritis.2 Plain radiography is only helpful in cases of ileus or megacolon.28

PHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

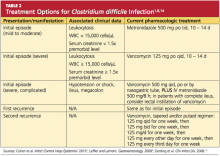

Discontinuation of the offending drug (usually an antibiotic), whenever possible, is the first step; up to 25% of CDI patients recover without any further therapies. Limiting management to antibiotic withdrawal, however, is currently recommended only in patients with the mildest form of CDI due to the risk for subsequent fulminant disease and clinical deterioration.14 In patients with suspected severe (but unconfirmed) CDI, empiric treatment with one of the antimicrobial agents listed below may be appropriate5 (see also Table 21,8,14). For patients with confirmed illness who require continued antimicrobial therapy, an agent not associated with CDI may be substituted (eg, sulfamethoxazole, macrolides, aminoglycosides).14

Metronidazole is the first-line agent for mild-to-moderate initial disease.1 The mechanism of action is through DNA disruption and inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis, a process that induces cell death. Metronidazole also appears to have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulating properties that assist in overcoming the disease. It should not be used in women who are pregnant.8

Dosage of the drug is 250 mg four times per day or 500 mg three times a day, given orally; or parenterally, if the patient cannot take it orally. The duration is 10 to 14 days (or longer in patients with underlying infection),1 and the cost is much lower than that of other appropriate antimicrobial agents (ie, less than $1/day).2,31

In patients with severe or refractory disease, vancomycin should be used. Vancomycin has shown superiority in severe disease compared with metronidazole, with clinical cure rates of 97% and 76%, respectively.1,4,32 The typical oral dosage is 125 mg four times per day for 10 days.1