In a study of young men who had worked as denim sandblasters, nearly all developed silicosis, while most had evidence of radiographic progression and/or significant lung function loss more than 4 years after their exposure to silica dust had ended.

The findings, published in the September issue of CHEST, derive from a study of 145 former sandblasters first identified in Turkey in 2007. At that time all had already ended their work as sandblasters at various facilities at least 10 months prior, and some had worked as little as a month. Mean age in the cohort was under 24 years in 2007, and first exposures occurred before a mean 18 years of age (CHEST 2015;148[3]:647-54).

In 2011, Dr. Metin Akgun and colleagues at Atatürk University in Erzurum, Turkey, revisited this cohort for follow-up and found that nine of the subjects had died. The researchers identified 83 of the surviving subjects and were able to conduct chest radiographs and spirometry on 74.

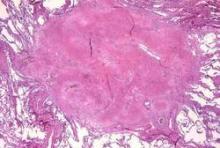

Dr. Akgun and colleagues sought to determine whether the silicosis cases, based on the International Labor Organization definitions of silicosis, had increased beyond the 53% seen in 2007, and measured pulmonary function loss and radiographic progression 4 years later.

The researchers found evidence of significant (more than 12%) pulmonary function loss in 66% of the follow-up cohort, and radiographic progression in 82%. Silicosis was found in all but one subject. Mean total length of exposure to silicone dust was about 3.5 years for this group, though no subject had been exposed after 2007.

Of the 74 living sandblasters available for reexamination, the prevalence of silicosis increased from 55.4% to 95.9%.

The findings, Dr. Akgun and colleagues wrote, confirmed that silicosis could develop without further exposure to silica dust after a course of work in denim sandblasting.

Younger age and younger age at first exposure were significantly associated with radiographic progression, the researchers found. Progression, pulmonary function loss, and mortality were associated with having worked as a foreman and with sleeping at the workplace, both indicative of higher exposure.

The nine subjects who died between 2007 and 2011 were more likely to have worked in more factories, to have been younger when first exposed, and never to have smoked.

Although Turkey banned silica sandblasting of denim jeans in 2009 in response to silicosis concerns, “the occupational health consequences are global as long as sandblasted jeans are sold, because production has shifted to other countries, including Bangladesh,” the researchers wrote in their analysis, recommending that clothing manufacturers “clarify their policies on purchasing sandblasted denim in light of the mortality and morbidity from silicosis associated with this process in the global supply chain.”

Dr. Akgun and colleagues noted that their study was limited by their inability to recruit the remaining 62 workers they had first seen in 2007, of whom a higher percentage were foremen. This reduced their ability to evaluate in more detail the differences in outcomes by exposure level.

Also, they noted, tuberculosis tests and sputum cultures were not performed at follow-up, leading to the possibility that mycobacterial infection may have affected disease progression in some subjects.

The authors disclosed that hey had no outside funding or conflicts of interest related to their findings.