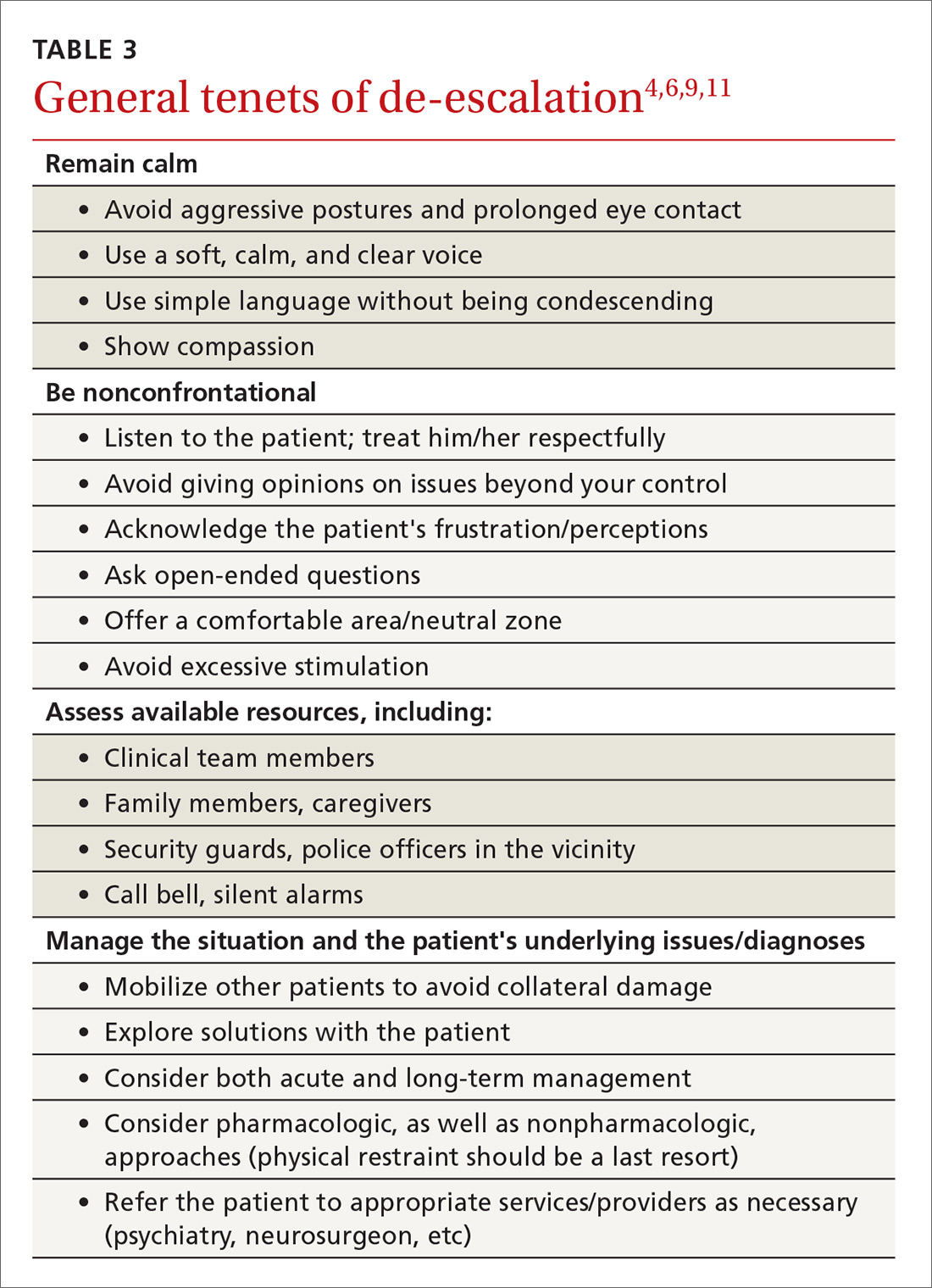

De-escalating the situation. General tenets of de-escalation apply across practice settings. Among them:

- Stay calm. Avoid aggressive postures and prolonged eye contact.

- Be nonconfrontational. Acknowledge the patient’s frustration/perceptions and ask open-ended questions.

- Assess available resources such as clinical team members, family members, and silent alarms.

- Manage the situation and the patient’s underlying issues/diagnoses. This includes mobilizing other patients to avoid collateral damage and exploring solutions with the patient.

For more on de-escalation tools, see (TABLE 34,6,9,11).

Your setting matters. It’s worth noting that the settings in which clinicians practice greatly influence the resources available to de-escalate a situation and ensure the safety of the patient and others.7 The review that follows provides some issues—and tips—that are unique to different practice settings.

Ambulatory settings

Sim and colleagues9 noted that aggressive behavior in the general practice setting may stem not only from factors related to the patient’s own physical or psychological discomfort, but from patients feeling that they are being treated unfairly, whether it be because of wait times, uncomfortable waiting conditions, or something else. A number of international studies have shown high rates of abuse toward FPs.9,12 Of 831 primary care physicians surveyed in a German study, close to three-quarters indicated that within the last year, they had experienced aggression (ranging from verbal abuse and threats to physical violence and property damage) from a patient.12 This statistic increased to 91% when it included the length of their career.

Bell13 suggests that physicians be aware that transference and countertransference issues are often at play when dealing with hostile or potentially violent patients. Suggestions to prevent aggression include some practice-level approaches (eg, providing waiting room distractions, making patients aware of potential delays), as well as being aware of nonverbal cues suggesting increased agitation (eg, clenched fists, crossed arms, chin thrusts, finger pointing).9

Group practice

An FP who practices with other health care providers and clinical staff has a built-in team that can assist with de-escalation. When meeting with a patient who has a history of violence or agitation in an exam room or office, try to ensure that you can get to an exit quickly if necessary. Also, alert staff to any concerns, and have a system for at least one staff member to check in periodically during the visit.

It is also helpful to develop an evacuation plan and create a “panic room” or “safe zone” for emergencies.14,15 Such a space may be nothing more than an area or room for staff to gather. It should have access to the police or other emergency services via a land and/or cell phone line.

Solo practice

If you practice alone, institute safeguards whereby a colleague (at a different practice, building, or location) can be alerted if concerns arise. In addition, consider the following precautions: locking the door when alone after hours, screening potential patients, having a way to call for help (keep the number for the local police station and ED readily available), prohibiting potential weapons (as some states allow them to be carried), and learning some form of self-defense.15

Resources exist that offer guidelines for developing policies and procedures, checklists, and sample incident forms (eg, the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety; iahss.org). Other organizations that can help with the development of a preparedness plan include the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/workplaceviolence/evaluation.html), the Department of Homeland Security (https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ISC%20Violence%20in%20%20the%20Federal%20Workplace%20Guide%20April%202013.pdf), and The Joint Commission (https://www.jointcommission.org/workplace_violence.aspx).