SAN DIEGO – Before treating Clostridium difficile, ask which test was used for diagnosis. For methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, know that linezolid is now in the arsenal and that vancomycin dosing has changed.

These words of advice came from Dr. John Bartlett, professor of medicine and former chief of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, at a session on recent developments in infectious disease.

"When somebody tells you a patient has a positive C. difficile test, or a negative C. difficile test, your next question is ‘what test,’ " Dr. Bartlett said.

About half of U.S. hospitals use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to diagnose C. diff., the other half, enzyme immunoassay (EIA), he said.

"PCR is exquisitely sensitive. It is very good for ruling it out, but there [are] false positives. EIA goes in the opposite direction. It’s not sensitive; it’s pretty good for specificity, [but] remember that if it’s a negative EIA, you have not excluded the diagnosis. EIA rules it in, PCR rules it out."

Increasingly, patients are colonized with C. diff. before they reach the hospital, probably from previous health care contact. Avoiding proton-pump inhibitors and antibiotics associated with C. diff. infection – cephalosporins, clindamycin, and fluoroquinolones – are wise moves for high-risk patients. Opiates should be avoided, too, because they cause intestinal stasis, he said.

It might take a while for the infection to respond to antibiotics; fecal transplantation is quicker.

"Fecal transplant is hot," Dr. Bartlett said. "The aesthetics" are lacking, but "it really works. Take a patient who has 10 relapses of C. diff., put in somebody else’s stool" – often delivered as a slurry through a nasogastric tube – "and the next bowel movement is normal. The biologic response is fantastic. It’s mostly done for patients who have multiple relapses, but it’s also been done in very refractory patients and those who are seriously ill," Dr. Bartlett said (Anaerobe 2009;15:285-9).

There’s a new colon-sparing surgical option for critically ill patients, diverting loop ileostomy with colonic lavage. Mortality rates are substantially lower, compared with traditional colon resection (Ann. Surg. 2011;254:423-7).

"You look at it and you say, ‘My God, why didn’t they think of this before?" Dr. Bartlett said.

There’s a new antibiotic choice, as well, after the Food and Drug Administration approved fidaxomicin for C. diff. in 2011. It has about the same cure rate as oral vancomycin, but fewer relapses, which may be "where this drug plays an important role," Dr. Bartlett said (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:422-31).

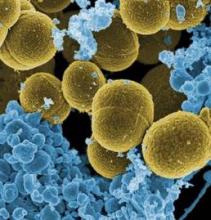

For methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) pneumonia, it’s important to remember that dosing guidelines have changed for treating bacterium with vancomycin, he said.

"Five years ago, everybody with MRSA got one gram twice a day. Now we are saying give vancomycin in a dose that achieves a trough level of 15-20 mcg/mL; if the minimum inhibitory concentration is" greater than 2 mcg/mL, "maybe you ought to give something else," he said (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:325-7; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:285-92).

And there now appears to be an alternative to vancomycin on the MRSA scene, Dr. Bartlett explained. In a head-to-head trial, linezolid "looked at least as good as vancomycin. There ought to be a comfort zone for that drug in MRSA pneumonia" (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:621-9).

The USA300 strain now accounts for about 30% of hospital MRSA infections; the balance remain mostly "the old USA100 strain. MRSA acquired outside the hospital is more likely to be USA300, inside the hospital more likely to be USA100.

"There’s not an awful lot you need to know about the differences between them," except [that] USA300, in addition to being sensitive to USA100 antibiotics, can also be treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, and clindamycin, Dr. Bartlett said.

Dr. Bartlett said he has no relevant financial disclosures.