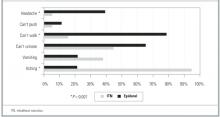

FIGURE 2

Side effects of labor analgesia: percentage of women reporting the symptom in each treatment group

Discussion

Evidence-based practice guidelines developed for obstetric analgesia by the American Society of Anesthesiologists are equivocal regarding the analgesic efficacy of spinal opioids compared to epidural local anesthetics.5 Within the limitations of a non-randomized study, our data indicate that intrathecal morphine and fentanyl (ITNs) provide less satisfactory pain control than a continuous epidural infusion of bupivacaine and fentanyl. This was true during the first and second stages of labor and on an overall pain rating from the first postpartum day. The limited duration of action of ITNs is likely to account for their lesser effectiveness. We found that the effective median duration of intrathecal morphine and fentanyl was between 60 and 120 minutes as determined by life table analysis of VAS scores.

Prior studies have evaluated intrathecal opioids in the context of combined spinal epidural analgesia and found the time to request for additional pain medication to be 90 to 150 minutes, with variation depending on which opioid was used and whether a local anesthetic was added.2,3,15 Although our clinical experience is that most women are grateful for 2 to 3 hours of relief from pain during active labor, our participants’ satisfaction with pain management was clearly related to the worst pain they experienced during labor, which in turn influenced their view of the overall effectiveness of the analgesic they received. This finding is similar to that of a survey of 1000 Australian women, where inadequate pain relief was the most frequent cause of dissatisfaction with the childbirth experience as a whole.16

Given our results, it seems reasonable to ask why stand-alone ITNs have become as popular as they have in certain hospital settings. One possibility is that they have offsetting benefits in terms of greater ease of administration and lower cost than epidural analgesia. Community and military hospitals that use ITNs as a sole method cite just such logistical advantages.7-9 Compared to epidural analgesia, ITNs are technically easier to administer and place fewer demands on nurses, obstetricians, and anesthesia personnel.7 In smaller and more rural hospitals that do not have anesthesiologists on staff, anesthetists, obstetricians, or family physicians may perform the spinal injection and safely monitor patients following ITNs.7,17

A second possibility is that ITNs offer the advantage of fewer side effects than epidural analgesia. Our data illustrate the differing side effect profiles of the 2 methods and support the conclusion that there is a trade-off among the expected side effects of opioids and local anesthetics rather than a clear advantage for ITNs. Women receiving intrathecal opioids were subjectively more satisfied with their ability to walk, but they were no more satisfied with their ability to push in the second stage than were women receiving epidural analgesia. It is possible that factors other than motor blockade—such as the constraints of monitors, catheters, and intravenous lines—prevented women in the epidural group from being satisfied with their ability to ambulate. Although the link between reduced motor blockade and fewer operative deliveries is controversial,18 ambulation in labor has been shown to foster a sense of control and improve maternal satisfaction.19,20

Finally, our data indicate that ITNs are an excellent analgesic for a subset of women who deliver rapidly. Studies of combined spinal epidural analgesia have also documented a significant proportion of women who are able to deliver with ITNs alone. In an early case series, 9 (60%) of 15 women receiving intrathecal morphine and fentanyl delivered without any epidural drugs, with pudendal nerve block for perineal anesthesia.2 In 2 recent combined spinal epidural trials, intrathecal sufentanil provided adequate analgesia as a sole agent in 16% to 20% of nulliparous women and in 45% of parous women.4,15

Our observational study is limited by the nonrandomized, nonblinded allocation of the 2 treatments. Observational studies are often viewed as subject to bias due to unrecognized confounders. As noted earlier, women in our study were reluctant to accept randomization and tended to be influenced toward a choice of ITNs due to an institutional history of preference for that method. It is possible that women choosing epidural analgesia in an environment favoring ITNs would be more likely to justify their choices with positive responses during a postpartum interview. However, it seems less likely that the large differences in VAS scores obtained during labor were so influenced. In addition, we used regression analysis to control for several factors shown in others studies to be associated with labor pain.10,21,22

Conclusion

Should ITNs be used as a sole labor analgesic? For hospitals with limited analgesic options, stand-alone ITNs can be a simple and effective method that improves pain management compared to parenteral opioids. Selecting appropriate candidates for ITNs and refraining from offering them too early in labor can improve their success. For hospitals with a full range of analgesic options, the appropriate use of stand-alone ITNs will spare some women added restrictions and side effects compared to continuous epidural analgesia and may improve their satisfaction with mobility. Ultimately, the choice of analgesia for labor rests with the woman herself. True informed consent means that all available options, including stand-alone ITNs, have been presented.