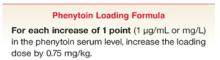

- To load phenytoin initially or to add a supplemental load, use this formula: for each μg/mL desired increase in the phenytoin serum level, increase the loading dose by 0.75 mg/kg (C).

- Measure the peak serum level shortly after loading—30 to 60 minutes or more after giving intravenous phenytoin, 2 hours or more after intravenous fosphenytoin, 4 hours or more after intramuscular fosphenytoin, and 16–24 hours after accelerated oral loading (C).

- The daily maintenance dose (mg/kg/d) ordinarily needed to achieve a specified serum level or maintain it after loading is calculated thus: (8 x target serum level)/(6 + target serum level) (C).

- Safe practice for initiating or adjusting a maintenance dosage should include patient education and close follow-up (C).

Despite the introduction of new anticonvulsant drugs, phenytoin is still a first-line medication for common types of epileptic seizures, particularly those caused by focal brain lesions.1-4 Available in parenteral and oral form, phenytoin (or its pro-drug, fosphenytoin) is widely used. An estimated 873,000 prescriptions for phenytoin were issued during office visits in 2001.5

Phenytoin carries a special risk of dose-related toxicity, due to its saturation (zero-order) pharmacokinetics: serum levels often rise much more than would ordinarily be expected after initiating or increasing a maintenance dose. This predicts a vulnerability to toxicity, but does not predict exactly when this will occur in the individual.

The risk of toxicity can be minimized, however, by applying practical dosing and monitoring strategies based on the understanding of phenytoin pharmacokinetics, and by educating patients appropriately.

Patients at risk: the scope of the problem

Extrapolating from the more than 5000 hospitals in the US6 to our experience in an urban community hospital, we estimate there may be as many as 25,000 cases of phenytoin intoxication presenting annually to emergency departments or resulting in hospitalization in the United States. In 1 study, a tertiary hospital recorded phenytoin intoxication from all causes at a rate of 1 inpatient admission per month over a 10-year period.7 Another study at a major hospital found 143 instances of phenytoin levels >25 μg/mL in 1 year; 86% of 120 studied cases were toxic, representing 33% of all adverse drug reactions reported.8 Thus, evidence points to a substantial problem with patient safety nationwide.

Adverse drug events like phenytoin intoxication increase morbidity, causing such injuries as falls due to ataxia and resulting in expenses of office or emergency department visits and hospitalization. While no prescription strategy, system of monitoring, or “safety net” is likely to eliminate phenytoin mishaps, an informed and active approach to therapeutic management can minimize instances of intoxication.

Action points and safety tips in phenytoin therapy

Safe therapy with phenytoin depends on observing particular courses of action at 4 stages:

- Loading

- Institution of a maintenance regimen

- Adjustment of the regimen

- Monitoring, follow-up, and patient education.

Loading

Loading is indicated when the risk of seizures is so great that adequate serum levels of the drug must be reached rapidly. Such situations would include status epilepticus; repeated new seizures (excluding most withdrawal seizures, for example); breakthrough seizures with a low anticonvulsant level; and a first seizure with a high likelihood of repeating, as with a demonstrated focal brain lesion. Depending on the degree of urgency, loading can be accomplished with intravenous phenytoin (at an infusion rate of no more than 50 mg/min), with intravenous or intramuscular fosphenytoin, or with oral phenytoin.

To load initially, or to add a supplemental load to increase an insufficient phenytoin level, the following formula based on a distribution constant for phenytoin indicates the amount of drug needed to raise the level by a specified amount.9

Use the loading formula. The peak serum level of phenytoin after intravenous loading is a function of the drug’s distribution in the body and is independent of the pharmacokinetics of elimination. Subsequent metabolism, which may be affected by other drugs or impairments (eg, liver disease), will affect elimination of the loaded drug but not ordinarily the calculated loading dose. Overloading phenytoin has been documented as a cause of early toxicity.7 According to the formula above, a 60-kg patient with no detectable starting level and an (arbitrary) target serum level of 15 μg/mL should need only 675 mg of phenytoin, and not the 1000 mg often administered.

This loading formula is also applicable to supplementary (“booster”) loading to reach a higher serum level quickly, either because the initial loading dose did not achieve the intended level or because that level was inadequate to control seizures. In this context, simply increasing the existing or planned daily maintenance dose raises the level too slowly. In addition, the increased maintenance dosage may be inappropriate if the cause of the low level is noncompliance. A higher maintenance dose, under conditions of complete or improved compliance, probably will lead to toxicity.