Basal/bolus: A better approach

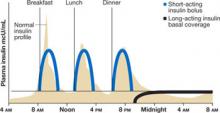

Mr. H’s physician started him on a basal/ bolus insulin regimen, which is more aggressive than a sliding-scale protocol and, as such, has prompted some physicians to view it warily. This strategy, in which a basal dose of long-acting insulin—typically given at bedtime—is accompanied by boluses of short-acting insulin at mealtimes,1,10-12 follows the normal physiological release of insulin (FIGURE 1). Basic metabolic insulin is required to cover endogenous hepatic glucose production, even among diabetes patients who are NPO, and prandial insulin requirements are determined by exogenous glucose intake, whether in the form of a meal, intravenous (IV) fluids, tube feeding, or total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Dosing guidelines. For most patients with type 2 diabetes, the correct daily insulin dose is 0.5 to 0.7 U/kg,1,13 but factors other than weight also need to be considered:

- Previous insulin use. A lower initial dose (0.4 U/kg/d) may be preferable for insulin-naive patients, whereas a higher dose (0.7 U/kg/d) may be necessary for those with a history of insulin resistance.1,3

- Risk of hypoglycemia. To be on the safe side, start patients who are at high risk of hypoglycemia (eg, because they are very lean, have hepatic or renal failure, or are undergoing hemodialysis) with a very low dose (0.3 U/kg/d).

- Other drugs or TPN regimen. A higher dose (0.7 U/kg/d) is appropriate for patients on high doses of steroids.1,3 Even smaller doses of oral or IV glucocorticoids increase the risk of hyperglycemia, particularly after a meal. Patients receiving TPN or other enteral feedings may also require higher doses of insulin.

Doing the math. To determine specific insulin requirements, calculate the total daily dose and divide it in half. The patient should receive half of the total as long-acting insulin for basal coverage, usually at bedtime. Divide the remaining half into 3 equal portions; administer each portion as a short-acting insulin bolus with each meal.1,3,10,11

Mr. H’s insulin requirements. Mr. H weighs 100 kg (220 pounds), so he needs 60 units (0.6 U/kg) of insulin per day. His physician writes an order for 30 units (one half of 60 units) of a long-acting insulin (glargine or detemir) at bedtime, and 10 units (one third of the remaining 30 units) of a short-acting insulin (as-part, lispro, or glulisine) with each meal (FIGURE 2).14

FIGURE 1

Basal/bolus regimen mimics normal insulin profile

Source: Polonsky KS, et al. J Clin Invest.12

FIGURE 2

Insulin types and duration

NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn.

Source: Hirsch B. N Engl J Med.14 Copyright 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society.

More insulin needed? Figuring out how much

It’s not unusual for patients on a basal/bolus regimen—particularly those like Mr. H, who have never been on insulin—to need supplemental insulin.15 Short-acting insulin is always used for this purpose, whether it is administered before a meal or at bedtime.

If a patient is hyperglycemic (>150 mg/dL) before a meal, a correction scale (TABLE) can be used to determine how much additional insulin to give. The supplemental insulin should be given at the same time as the mealtime bolus.

If hyperglycemia is detected at bedtime, a more conservative approach is needed to prevent overnight hypoglycemia. Thus, additional insulin is recommended at bedtime only if the blood glucose reading is >200 mg/dL, and approximately half of the recommended mealtime correction dose should be given.16

TABLE

Insulin correction scale: Calculating the supplemental dose

| BLOOD GLUCOSE mg/dL | EXTRA INSULIN | |

|---|---|---|

| PREMEAL (NO. OF UNITS) | BEDTIME (NO. OF UNITS) | |

| 150-199 | 1 | None |

| 200-249 | 2 | 1 |

| 250-299 | 3 | 2 |

| 300-349 | 4 | 2 |

| ≥350 | 5 | 3 |

| Source: Walsh J, et al. Torrey Pines Press.16 | ||

Is it time to revise the dosing regimen?

Consistent use of a correction scale to adjust the dosage generally indicates that the patient’s baseline dosing regimen needs to be revised. Dynamic insulin coverage requires careful monitoring, with blood glucose levels recorded and reviewed for trends that suggest a change is needed.

Poor subcutaneous perfusion, for example, may lead to a decreased or erratic uptake of injected insulin. Also, stress-related hyperglycemia may decrease or increase over the course of a hospital stay. And changes in medication, such as a decreasing steroid taper, may change overall insulin demand.15,17

With vigilant monitoring, the basal/bolus regimen may be adjusted upward to 110% of current dosing for a patient with frequent elevated blood glucose readings—provided the patient’s glucose levels have not fallen below 80 mg/dL. Conversely, the regimen may be adjusted downward to 80% for a patient who continues to be hypoglycemic. Unlike the supplemental dosing based on the correction scale, these revised regimens affect both the basal (long-acting) and bolus (short-acting) doses.