• Treat burning foot pain in patients with diabetes with tricyclic antidepressants or anticonvulsants. A

• Prescribe custom-fitted extra-depth shoes for patients with diabetes and neuropathy or foot deformity. B

• Consider hyperbaric oxygen therapy for ulcers that fail to respond to standard therapy. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE: AN OBESE PATIENT WITH BURNING FOOT PAIN

Mr. F., an obese 47-year-old with hypertension and type 2 diabetes, is trying to lose weight, and comes in to discuss a new exercise program. He recently had a negative cardiac workup for chest pain, which was ultimately diagnosed as gastroesophageal reflux disease.

The patient, whose most recent glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is 7.5, reports painful burning in his feet at night. A foot exam reveals no ulcers, lesions, or calluses; 2+ dorsalis pedis pulses bilaterally; and loss of sensation to 10-g monofilament testing at 3 sites on the bottom of each foot.

Based on Mr. F.’s presentation, it seems safe from a cardiac standpoint for him to embark on an exercise program, but what about his risk for a foot ulcer? An accurate assessment would enable you to tailor your recommendations and take the appropriate steps to modify the patient’s risk now—and to minimize complications down the road.

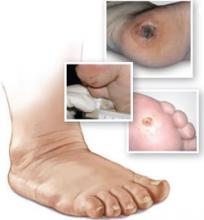

The incidence of diabetic foot ulcers—like that of diabetes itself—has risen in recent years.1 More than 15% of the approximately 23.5 million US adults with diabetes are expected to develop a foot ulcer at some point in their lives.2 Improvements in wound care and increased use of revascularization techniques have led to a decline in the number of ulcer-related amputations.3 But for 7% of those who develop diabetic foot ulcers, amputation is still the end result.4

As a family physician, you can play a key role in guarding against that outcome. This review—and the risk classification, ulcer grading, and treatment mnemonic tools that are detailed in the pages that follow—will help you optimize the foot care you provide to patients with diabetes.

Simple classification system accurately predicts risk

The longer an individual lives with diabetes and the poorer the level of blood glucose control, the greater the risk of ulceration.1,5 Other major risk factors include neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease, and a previous foot ulcer or amputation. All patients with diabetes should undergo an annual risk assessment for foot ulcers, which can be easily incorporated into their yearly physical. Although the causes of ulceration are numerous and complex, classification of risk based on simple measures has been found to accurately predict risk.6

Risk stratification tool. Medical history and in-office assessment of pulses, sensation, and foot deformities form the basis for a handy assessment tool (TABLE 1). In a study of 3256 patients, these simple criteria successfully predicted ulcer risk. During the nearly 2 years of the study, fewer than 1% of those categorized as low risk (n=2253) developed ulcers, while more than 29% of the high-risk group (n=477) did.6

To assess a patient’s risk, visually examine both feet, inspecting the skin, nails, and structure. Autonomic neuropathy may cause decreased sweating, leading to dry, breakable skin, while motor neuropathy can cause deformities such as hammer or claw toes, which also increase ulcer risk. Palpate for dorsalis pedis and posterior tibialis pulses. Although posterior tibialis pulses may be congenitally absent, the absence of a dorsalis pedis pulse is associated with a 6-fold increased risk of foot ulcer.1

Compared with patients with diabetes who have never had a foot ulcer, patients with a history of foot ulcer have 13 times the risk.7 As already noted, glucose control is also a key risk factor. For every 2-point increase in HbA1c, the odds ratio for ulcer development increases by 1.6,5 which is likely the result of hyperglycemia’s contribution to microvascular disease and peripheral neuropathy.

TABLE 1

Diabetic foot ulcer: Risk stratification

| Risk level/criteria | Incidence of ulcer* |

|---|---|

| Low risk All of the following: No history of ulcer At least 1 pulse per foot ≤1 of 10 sites insensate to monofilament testing No foot deformity or physical or visual impairment | 0.36% |

| Moderate risk 1 or more of the following: Missing both pulses in either foot ≥2 insensate sites to monofilament testing Foot deformity Unable to see or reach foot | 2.3% |

| High risk 1 or more of the following: Prior ulcer or amputation Neuropathy and absent pulses Neuropathy or absent pulses and calluses or foot deformity | 29.4% |

| * Percentage of patients in each risk category who developed foot ulcers over the nearly 2-year study period. | |

| Source: Leese GP, et al. Int J Clin Pract. 2006.6 | |