Order ultrasound of the scrotum and testes to evaluate chronic testicular pain, with color Doppler to identify areas of hypervascularity. C

Treat suspected epididymitis with empiric coverage for chlamydia with either a 10-day regimen of doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) or a single dose (1 g) of azithromycin; treat suspected gonorrhea with a single intramuscular injection (125 mg) of ceftriaxone. A

Do not treat small epididymal cysts that do not correlate with testicular pain; larger, painful cysts can be aspirated, injected with a sclerosing agent, or surgically excised. C

Consider surgical options only after medical and conservative therapies have failed to alleviate chronic testicular pain. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 Vincent B, a 33-year-old executive, visits his family physician for an evaluation of chronic orchialgia. Although his testicular pain has waxed and waned for several years, it has recently worsened, making it increasingly difficult for him to exercise or to sit for extended periods of time. In fact, this visit was prompted by a lengthy meeting during which he developed a “dull ache” that did not let up until he left the meeting and walked around.

CASE 2 Jason H, a 42-year-old married father of 3 who had a vasectomy 2 years ago, has had progressively worsening testicular pain ever since. He also has occasional pain after ejaculation, but no known hematospermia. Recently, the pain has become so bad that it limits both his physical and sexual activities and is having a negative effect on his relationship with his wife. Jason is sexually monogamous, has no significant medical history, and takes no prescription medications.

These 2 cases are based on actual patients we have seen in our practices. If Vincent and Jason (not their real names) were your patients, how would you initiate a work-up for testicular pain? What treatments would you offer? And at what point would you consider a referral to a urologist?

Chronic orchialgia is a complex urogenital focal pain syndrome in which neurogenic inflammation is the principal mediator. This debilitating condition is associated with substantial anxiety and frustration, and is characterized by intermittent or constant unilateral or bilateral testicular pain, occurring for at least 3 months, that has a significant negative impact on activities of daily living and physical activity.1

A variety of procedural and surgical options may help to minimize or alleviate chronic orchialgia. But which approach is best? There are no evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of this condition, and no randomized controlled trials to demonstrate the superiority of 1 modality over another. All diagnostic and treatment recommendations are based on expert opinion derived from small cohort studies.

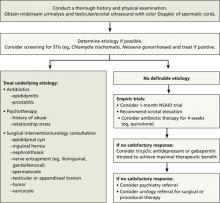

With that in mind, we conducted a systematic review of the literature evaluating medical and surgical therapies for chronic testicular pain—and developed an algorithm (FIGURE 1), along with the text and TABLE that follow, for family physicians (FPs) to use as a guide.

FIGURE 1

Chronic orchialgia: A diagnosis and treatment algorithm1,3,4,6,10

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

CASE 1 Vincent B

Over the last few years, Vincent has had similar episodes of bilateral testicular pain. He denies any history of direct trauma to the testicles, and he works out regularly by lifting weights and running. When the pain becomes unbearable, he takes acetaminophen or ibuprofen and takes a few days off from exercising, which provides modest—but temporary—relief.

Vincent reports that he has had about a dozen lifetime sexual partners and had chlamydia over a decade ago as a college student. He is currently engaged and sexually monogamous, and tested negative for Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, hepatitis, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) at his annual health maintenance examination last month. Shortly before that, Vincent was treated empirically for epididymitis with a 4-week course of ciprofloxacin, with no significant improvement in symptoms. He has no significant past medical history, denies depression, and takes no prescription medications.

Physical examination reveals mild to moderate diffuse tenderness to palpation throughout the scrotum, including both testicles and spermatic cords. There is no erythema of the scrotum. Nor are there any palpable scrotal masses, varicoceles, or hydroceles; testicular, scrotal, or penile lesions; inguinal masses; or lymph nodes. His urethral meatus is patent. The prostate is smooth, nonnodular, and non-tender. The remainder of the physical exam is unremarkable.

Determining a cause can be a challenge

There are numerous possible causes of testicular pain (TABLE), including an inguinal hernia, torsion of the testicle, trauma, and a history of chlamydia or gonorrhea, to name a few.