› Avoid scheduling annual visits exclusively for preventive care. A

› Institute simple practice changes to improve the preventive services you provide, such as implementing standing orders for influenza vaccines. A

› Adopt components of the chronic care model for preventive services wherever possible—using ancillary providers to remind patients to undergo colorectal cancer screening and recommending apps that support self-management, for example. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

For well over a century, the periodic health exam has been associated with the delivery of preventive services1—a model widely accepted by physicians and patients alike. Approximately 8% of ambulatory care visits are for check-ups, and more than 20% of US residents schedule a health exam annually.2

Periodic health exams, however, do not result in optimal preventive care. Evidence suggests that important preventive services, such as dietary counseling, occur at only 8% of such visits; that just 10 seconds, on average, is devoted to smoking cessation; and that 80% of the preventive services patients receive are delivered outside of scheduled health exams.2 Because physicians and patients alike understandably prioritize acute problems, any discussion of health maintenance issues during a periodic check-up is likely to occur despite the visit’s agenda, not as part of it.3-7

Primary care physicians and practices are increasingly being held accountable for their performance on preventive measures. With that in mind, being familiar with evidence-based guidelines relating to the delivery of preventive services in ambulatory care settings, such as those developed by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),8 is crucial. Identifying elements of the chronic care model that can be effectively applied to preventive care—and recognizing that the reactive acute care model is ineffective for both chronic illness and preventive services—is essential, as well.

Preventive care that's evidence-based

Good practice guidelines should have the following features, according to the Institute of Medicine:9

• Validity. Application would lead to the desired health and cost outcomes.

• Reliability/reproducibility. Others using the same data/interpretation would reach the same conclusion.

• Clinical applicability. Patient populations are appropriately defined.

• Clinical flexibility. Known or generally expected exceptions are identified.

• Clarity. Guideline uses unambiguous language with precise definitions.

• Multidisciplinary process. Developed with the participation of all key stakeholders.

• Scheduled review. Periodically reviewed and revised to incorporate new evidence/changing consensus.

• Documentation. Procedures used in development are well documented.

The USPSTF guidelines are consistent with these attributes.8

Some brief interventions fail

Guidelines are useful as practice standards for establishing preventive care goals, but their existence alone does not ensure the delivery of high-quality preventive services in an office setting. One key factor is time. It is estimated that a primary care physician with an average-sized patient panel would require an additional 7.4 hours per day to achieve 100% compliance with all of the USPSTF recommendations.10

Counseling, in particular, is an intervention that may be more effective in theory than in practice. Evidence suggests that even when primary care providers are trained in preventive counseling (and many are not), many brief interventions are not effective at creating sustained behavior change or health improvement.11

Others are effective

That’s not to say that there’s little that can be done. Use of standing orders for influenza vaccination is one example of an effective and easily implemented preventive measure that requires little or no additional physician time. Yet some doctors are resistant, fearing loss of control or lawsuits. In fact, the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program specifically provides protection against vaccinerelated malpractice claims.12 A standing order for office staff to arrange a screening mammogram is another effective intervention; it has been shown to improve screening rates by as much as 30%.13

Lessons from chronic illness management

Chronic illness care and preventive care have much in common.14 Both acknowledge the need for proactive screening and counseling to bring about behavior change. In addition, both require ongoing care and follow-up, as well as depend on links to community resources. And finally, both are resource-intensive—too resource-intensive, some say, to be delivered in a cost-effective manner.

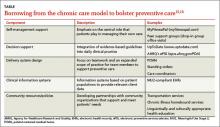

The Chronic Care Model has been proposed as a framework for improving preventive services (TABLE).15,16 Evidence suggests adopting some key components of chronic care can lead to significant gains in the delivery of preventive care, with the largest improvement seen when multiple components are used simultaneously.17-20