Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is “the inability to maintain wakefulness and alertness during the major waking periods of the day, with sleep occurring unintentionally or at inappropriate times, almost daily for at least 3 months,” according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.1 EDS is common, with a prevalence up to 25% to 30% in the general population.1-4 The prevalence rate varies in different studies, primarily because of inconsistent definitions of EDS, and therefore differences in diagnosis and assessment.1,2,4 In a study of 300 psychiatric outpatients, 34% had EDS.3 However, studies and evidence reviewing EDS in psychiatric patients are limited.

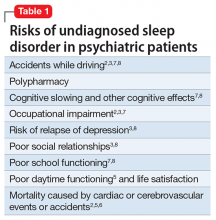

EDS can affect functioning in key areas of life, such as work, home, and school, and increases risk of morbidity and mortality (Table 12,3,5-8). Studies have indicated a link between EDS and psychiatric disorders, especially depression.3 However, the underlying etiology of EDS often is unrecognized in psychiatric practice, and many patients are misdiagnosed and prescribed psychotropic medications for their symptoms without an evaluation of the actual causes of EDS, which leaves the underlying condition unaddressed.5The causes of EDS are many and varied,1,8 including medical and psychiatric etiologies. A thorough history, screening at-risk patients, and timely sleep center referral are vital to detect and appropriately manage the cause of EDS.5

This article reviews the literature on EDS, with a focus on the risks of untreated EDS, common etiologies of the condition, as well as a brief description of screening and treatment strategies.

EDS vs fatigue

Many patients describe EDS as “fatigue”1; however, a patient’s report of fatigue could be mistaken for EDS.4 Although there is overlap, it is important for physicians to distinguish between these 2 entities for accurate identification and treatment.1,4

Risk of inadequate screening

A study of 117 patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease showed that EDS is associated with significantly greater incidence of cardiovascular adverse events at 16-month follow up.2 This study had limitations such as small sample size; therefore, more studies are needed. Because of these risks, timely and accurate diagnosis not only improves the patient’s quality of life and reduces polypharmacy but also can be life-saving.

Common causes of EDS in psychiatric patients

Because of the high prevalence and severity of impairments caused by EDS, it is essential for psychiatrists to be informed about causes of EDS and thoroughly assess for the potential underlying etiology before concluding that the sleep problem is a manifestation of the psychiatric disorder and prescribing psychotropic medication for it.

Some common causes of EDS in psychiatric patients include:

Sleep-disordered breathing.8 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is often underdiagnosed,6,7 and considering how common it is,6 psychiatrists likely will see many patients with OSA in their practice.5 OSA has a higher prevalence among patients with psychiatric disorders such as depression6,9 and schizophrenia. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that patients with OSA are more likely to suffer from depression and EDS than healthy controls6,9,10; some of the proposed mechanisms are sleep fragmentation and hypoxemia.6,9-11 OSA is the most common form of sleep-disordered breathing and is a common cause of EDS.1,2,12 Also, undiagnosed and untreated OSA in patients with depression could cause refractoriness to pharmacological treatment of depression.6,9,10

When unrecognized and untreated, OSA can be life-threatening. Despite this, OSA is not regularly screened for in clinical psychiatric practice.6,10 Therefore, it is imperative that psychiatrists be well-acquainted with measures to identify at-risk patients and refer to a sleep specialist when appropriate.

OSA is accompanied by irritability, cognitive difficulties, and poor sleep, creating an overlap with symptoms of depressive disorders.6,10 Use of sedative hypnotic medications, such as benzodiazepines, which further reduces muscle tone in the airway and suppresses respiratory effort, can worsen OSA symptoms5,6,10 and pose cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, and potentially life-threatening risks, and therefore is not indicated in this population.9,13