Other medical conditions,1 such as the rare familial fatal insomnia, neurological conditions1 such as encephalitis,8 epilepsy,8 Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia,8 Parkinson’s disease,1 or multiple sclerosis,1,18 can cause excessive daytime fatigue by causing secondary insomnia or hypersomnia.

Treating the underlying disorder is an important first step in these cases. In addition, coordinating with neurologists or other specialists involved in caring for patients with these conditions is important. Regularly reviewing and simplifying the often complex medication regimen, when possible, can go a long way in mitigating EDS in this population.

Other disorders affecting sleep. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder are other causes of EDS.3 Treatment involves lifestyle modifications, iron supplementation in certain patients, and use of dopaminergic agents such as ropinirole, pramipexole, and other medications, depending on severity of the condition, comorbidities, and other factors.20

Alcohol or substance use. Substance use or withdrawal can be associated with sleep disorders, such as hypersomnia,19 insomnia,19 and related EDS.5 For example, alcohol use disorder affects REM sleep, and can cause EDS. Secondary central apnea can be the result of long-standing opioid use19 and can present like EDS.

Insomnia. Primary insomnia rarely causes EDS.5 Insomnia due to a medical or psychiatric condition may be an indirect cause of EDS by causing sleep deprivation.

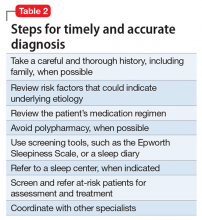

Steps for timely and accurate diagnosis

Utilize the following steps for facilitating timely diagnosis and treatment of EDS:

Thorough history. Patients often describe “tiredness” instead of sleepiness.8 Therefore, the astute psychiatrist should explore further when patients are presenting with this concern, especially by asking more specific questions such as the tendency to doze off during daytime.8

Family members can be vital sources for obtaining a complete history,5 especially because patients might deny,8 minimize, or not be fully aware1 of the extent of their symptoms. Asking family members about patient’s snoring, irregular breathing, or gasping at night can be particularly valuable.5 Obtaining a family history of sleep disorders can be particularly important, especially in conditions such as OSA and narcolepsy.

Asking about any history of safety issues,8 including sleepiness during driving, cooking, or other activities, is also important.

Use of scales and other screening measures. Psychiatrists can use initial screening measures in the office setting. Epworth Sleepiness Scale15,21 is a validated,2 short, self-administered measure to assess the level of daytime sleepiness; however, it has some limitations such as not being able to measure changes in sleepiness from hour to hour or day to day. Because of its limitations, the Epworth Sleepiness Scale should not be used by itself as a diagnostic tool.3 It has been commonly used for detecting OSA2 and narcolepsy. The Stanford Sleepiness Scale is a self-rating scale that measures the subjective degree of sleepiness and alertness; it has limitations as well, such as having little correlation with chronic sleep loss.8 Other tools such as visual analogue scales also could be helpful.8 For more specialized testing, such as Multiple Sleep Latency Test or polysomnography, referral to a sleep specialist is ideal.8

Education. The assessment is an opportunity for the psychiatrist to educate patients about sleep hygiene, the importance of regular bedtimes, and getting adequate sleep to avoid accumulating a sleep deficit.

Urgent referral of at-risk populations. Prompt or urgent referral of at-risk populations, such as geriatric patients or those with a history of dozing off during driving, is invaluable in preventing morbidity and mortality from untreated sleep disorders.

Patients with severe daytime sleepiness should be advised to not drive or operate heavy machinery until this condition is adequately controlled.18

Coordination with other specialists. Psychiatric patients are at higher risk for developing medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension, all of which may be linked with EDS because of various factors; therefore, psychiatrists should coordinate with other specialists, such as neurologists, primary care providers, sleep medicine physicians, and others, for risk detection, timely diagnosis, and care (Table 2).