HISTORY Command hallucinations

Postoperatively, Mr. K is managed in the trauma intensive care unit. During psychiatric consultation, Mr. K demonstrates a blunted affect. His speech is low in volume but clear and coherent. His thoughts are generally linear for specific lines of inquiry (eg, about perceived level of pain) but otherwise are impoverished. Mr. K often digresses into repetitively mumbled prayers. He appears distracted, as if responding to internal stimuli. Although he acknowledges the GSM, he does not discuss the factors underlying his decision to proceed with auto-penectomy. Over successive evaluations, he reluctantly discloses that he had been experiencing disparaging auditory hallucinations that told him that his penis “was too small” and commanded him to “cut it off.”

Psychiatric history reveals that Mr. K required psychiatric hospitalization 7 months earlier due to new-onset auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and thought disorganization, in the context of daily Cannabis use. At the time, the differential diagnosis included new-onset schizophrenia and substance-induced psychosis. His symptoms improved quickly with risperidone, 2 mg/d, and he was discharged in a stable condition with referrals for outpatient care. Mr. K admits he had stopped taking risperidone several weeks before the GSM because he was convinced that he had been cured. At that time, Mr. K had told his parents he was no longer required to take medication or engage in outpatient psychiatric treatment, and they did not question this. Mr. K struggled to sustain part-time employment (in a family business), having taken a leave of absence from graduate school after his first hospitalization. He continued to use Cannabis regularly but denies being intoxicated at the time of the GSM. Throughout his surgical hospitalization, Mr. K’s thoughts remain disorganized. He denies that the GSM was a suicide attempt or having current suicidal thoughts, intent, or plans. He also denies having religious preoccupations, over-valued religious beliefs, or delusions.

Mr. K identifies as heterosexual, and denies experiencing distress related to sexual orientation or gender identity or guilt related to sexual impulses or actions. He also denies having a history of trauma or victimization and does not report any symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder or body dysmorphic disorder.

The authors’ observations

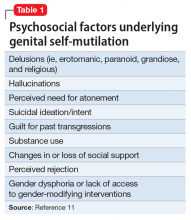

There are numerous psychological factors underlying and engendered by GSM.18-22 Delusions, hallucinations, a need for atonement, suicidal ideation, and subjective guilt have been reported among individuals engaging in GSM who have psychosis (Table 1).11 Severe forms of GSM, such as castration, occur among individuals who manifest more symptoms and greater severity of psychopathology.Little is known about how many individuals who engage in GSM eventually complete suicide. Although suicidal ideation and intent have been infrequently associated with GSM, suicide has been most notably reported among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and psychotic mood disorders.11,18,23-26 For these individuals, suicidal ideation co-occurred with delusions, hallucinations, and pathological guilt preoccupations. Significant self-inflicted injury can be harbinger of distress that could lead to suicide if not optimally treated. Other psychosocial stressors, such as disruptions in interpersonal functioning arising from changes in or loss of social support or perceived rejection, may contribute to a patient’s level of distress, complicating underlying psychiatric disturbances and increasing vulnerability toward GSM.11,27

Substance use also increases vulnerability toward GSM.11,18,24,28 As is the case with patients who engage in various non-GSM self-injurious behaviors,29,30 substance use or intoxication likely contribute to disinhibition or a dissociative state, which enables individuals to engage in self-injury.30

A lack of access to treatment is a rare precipitant for GSM, except among individuals with gender dysphoria. Studies have found that many patients with gender dysphoria who performed self-castration did so in a premeditated manner with low suicidal intent, and the behavior often was related to a lack of or refusal for gender confirmation surgery.31-34

In the hospital setting, surgical/urological interventions need to be directed at the potentially life-threatening sequelae of self-injury. Although complications vary, depending on the type of injury incurred, urgent measures are needed to manage blood loss because hemorrhage can be fatal.23,35,36 Other consequences that can arise include urinary fistulae, urethral strictures, mummification of the glans penis, and development of sensory abnormalities after repair of the injured tissues or reattachment.8 More superficial injuries may require only hemostasis and simple suturing, whereas extensive injuries, such as complete amputation, can be addressed through microvascular techniques.

The psychiatrist’s role. The psychiatrist should act as an advocate for the GSM patient to create an environment conducive to healing. A patient who is experiencing hallucinations or delusions may feel overwhelmed by medical and familial attention. Pharmacologic treatment for prevailing mental illness, such as psychosis, should be initiated in the inpatient setting. An estimated 20% to 25% of those who self-inflict genital injury may repeatedly mutilate their genitals.19,28 Patients unduly influenced by command hallucinations, delusional thought processes, mood disturbances, or suicidal ideation may attempt to complete the injury, or reinjure themselves after surgical/urological intervention, which may require safety measures, such as 1:1 observation, restraints, or physical barriers, to prevent reinjury.37

Self-injury elicits strong, emotional responses from health care professionals, including fascination, apprehension, and hopelessness. Psychiatrists who care for such patients should monitor members of the patient’s treatment team for psychological reactions. In addition, the patient’s behavior while hospitalized may stir feelings of retaliation, anger, fear, and frustration.11,24,37 Collaborative relationships with medical and surgical specialties can help staff manage emotional reactions and avoid the inadvertent expression of those feelings in their interactions with the patient; these reactions might otherwise undermine treatment.24,34 Family education can help mitigate any guilt family members may harbor for not preventing the injury.37

Although efforts to understand the intended goal(s) and precipitants of the self-injury are likely to be worthwhile, the overwhelming distress associated with GSM and its emergent treatment may preclude intensive exploration. Assessing precipitants of self-injury should be approached using a nonjudgmental, dispassionate, matter-of-fact manner that conveys concern for the patient38 and reassures the patient that the clinician has heard and, ideally, understands the patient’s distress.39 Forced exploration during the prevailing stress of treatment may overwhelm the patient, prove to be overly distressing, and compel the patient to act out in self-injurious ways. Therefore, exploration of the underpinnings of GSM may need to be postponed until surgical treatment is completed, the patient’s symptoms have been managed with psychopharmacologic intervention, and the patient has been transitioned to the safety and close monitoring of an acute psychiatric inpatient setting.