TREATMENT Restarting medication

While on the surgical unit, Mr. K is restarted on risperidone, 2 mg/d. He appears to tolerate the medication without adverse effects. However, because Mr. K continues to experience auditory hallucinations, and the treatment team remains concerned that he might again experience commands to harm himself, he is transferred to an acute psychiatric inpatient setting.

Urology follow-up reveals necrosis/mummification of the replanted penis and an open scrotal wound. After discussing options with the patient and family, the urologist transfers Mr. K back to the surgical unit for wound closure and removal of the replanted penis. A urethrostomy is performed to allow for bladder emptying.

The authors’ observations

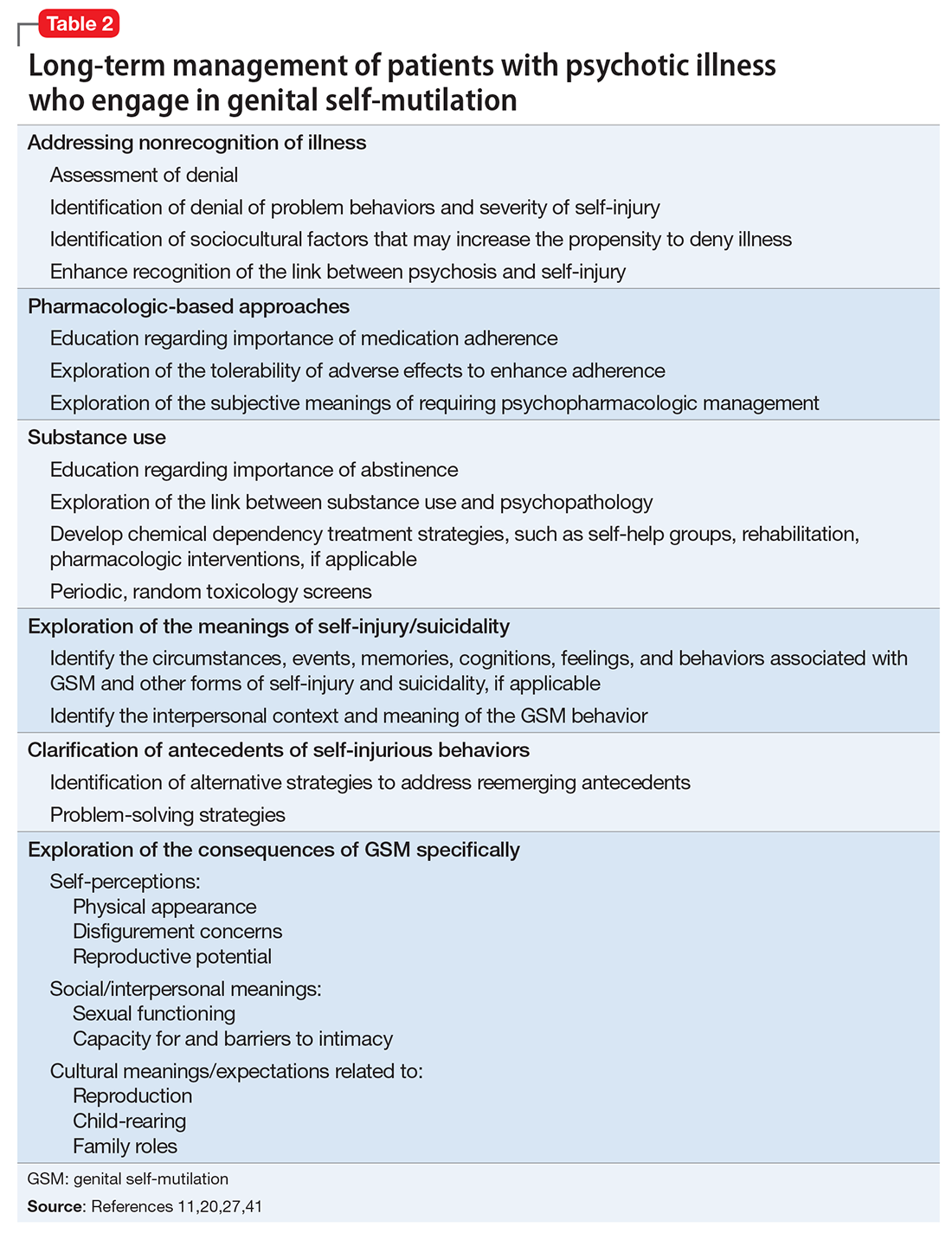

Because most published case reports of GSM among men have focused on acute treatment, there is a dearth of literature available on the long-term course of GSM to inform treatment strategies. Because recovery is a non-static process and a patient’s reactions to his injury will likely evolve over time, a multifaceted approach invoking psychiatric and psychotherapeutic interventions is necessary to help patients after initial injury and surgical management37,40-43 (Table 211,20,27,41).

OUTCOME Return to school, work

Mr. K is discharged with close follow-up at a specialized clinic for new-onset psychosis. Post-discharge treatment consists of education about the course of schizophrenia and the need for medication adherence to prevent relapse. Mr. K also is educated on the relationship between Cannabis use and psychosis, and he abstains from illicit substance use. Family involvement is encouraged to help with medication compliance and monitoring for symptom reemergence.

Therapy focuses on exploring the antecedents of the auto-penectomy, Mr. K’s body image issue concerns, and his feelings related to eventual prosthesis implantation. He insists that he cannot recall any precipitating factors for his self-injury other than the command hallucinations. He does not report sexual guilt, although he had been sexually active with his girlfriend in the months prior to his GSM, which goes against his family’s religious beliefs. He reports significant regret and shame for the self-mutilation, and blames himself for not informing family members about his hallucinations. Therapy involves addressing his attribution of blame using cognitive techniques and focuses on measures that can be taken to prevent further self-harm. Efforts are directed at exploring whether cultural and religious traditions impacted the therapeutic alliance, medication adherence, self-esteem and body image, sexuality, and future goals. Over the course of 1 year, he resumes his graduate studies and part-time work, and explores prosthetic placement for cosmetic purposes.

The authors’ observations

Research suggests that major self-mutilation among patients with psychotic illness is likely to occur during the first episode or early in the course of illness and/or with suboptimal treatment.44,45 Mr. K was enlisted in an intensive outpatient treatment program involving biweekly psychotherapy sessions and psychiatric follow-up. Initial sessions focused on education regarding the importance of medication adherence and exploration of signs and symptoms that might suggest reemergence of a psychotic decompensation. The psychiatrist monitored Mr. K closely to ensure he was able to tolerate his medications to mitigate the possibility that adverse effects would undermine adherence. Mr. K’s reactions to having a psychiatric illness also were explored because of concerns that such self-appraisals might trigger shame, embarrassment, denial, and other responses that might undermine treatment adherence. His family members were apprised of treatment goals and enlisted to foster adherence with medication and follow-up appointments.

Mr. K’s Cannabis use was addressed because ongoing use likely had a negative impact on his schizophrenia (ie, a greater propensity toward relapse and rehospitalization and a poorer therapeutic response to antipsychotic medication).46,47 He was strongly encouraged to avoid Cannabis and other illicit substances.

Psychiatrists can help in examining the meaning behind the injury while helping the patient to adapt to the sequelae and cultivate skills to meet functional demands.41 Once Mr. K’s psychotic symptoms were in remission, treatment began to address the antecedents of the GSM, as well as the resultant physical consequences. It was reasonable to explore how Mr. K now viewed his actions, as well as the consequences that his actions produced in terms of his physical appearance, sexual functioning, capacity for sexual intimacy, and reproductive potential. It was also important to recognize how such highly intimate and deeply personal self-schema are framed and organized against his cultural and religious background.27,33

Body image concerns and expectations for future urologic intervention also should be explored. Although Mr. K was not averse to such exploration, he did not spontaneously address such topics in great depth. The discussion was unforced and effectively left open as an issue that could be explored in future sessions.