Recent small studies have shown that MRI can detect renal microcysts in approximately 100% of patients who are receiving chronic lithium treatment and have renal insufficiency. One MRI study found renal microcysts in all 16 patients.33 In another MRI study of 4 patients, all were positive for renal microcysts.34 The relationship between MRI findings and renal function impairment in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy is still not clear; however, 1 study that examined 35 patients who received lithium reported that the number of cysts is generally related to the duration of lithium therapy.35 Thus, microcysts seem to present long before the elevation in creatinine, and nearly always present in patients with some glomerular dysfunction.

Cystic renal lesions have a wide variety of differential diagnoses, including simple renal cysts; glomerulocystic kidney disease; medullary cystic kidney disease and acquired cystic kidney disease; and multicystic dysplastic kidney and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.36 In patients who have a long history of lithium use, lithium-related nephrotoxicity should be added to the differential diagnosis. The ubiquitous presence of renal microcysts and their relationship to duration of lithium exposure and renal function suggest that they may be intimately related to lithium-related ESRD.37

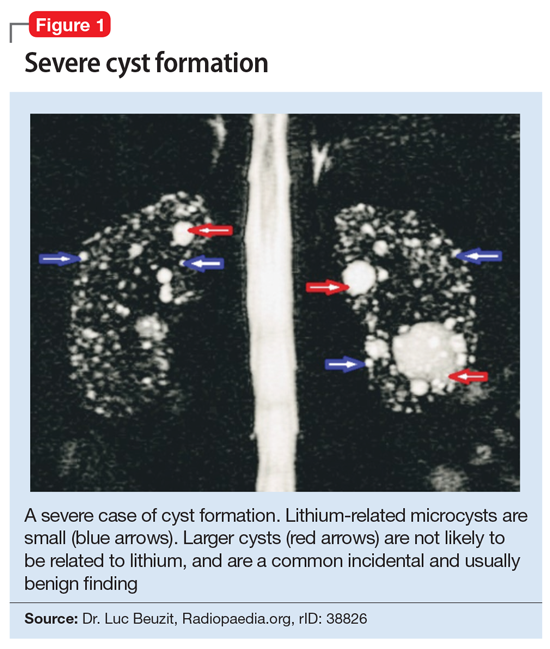

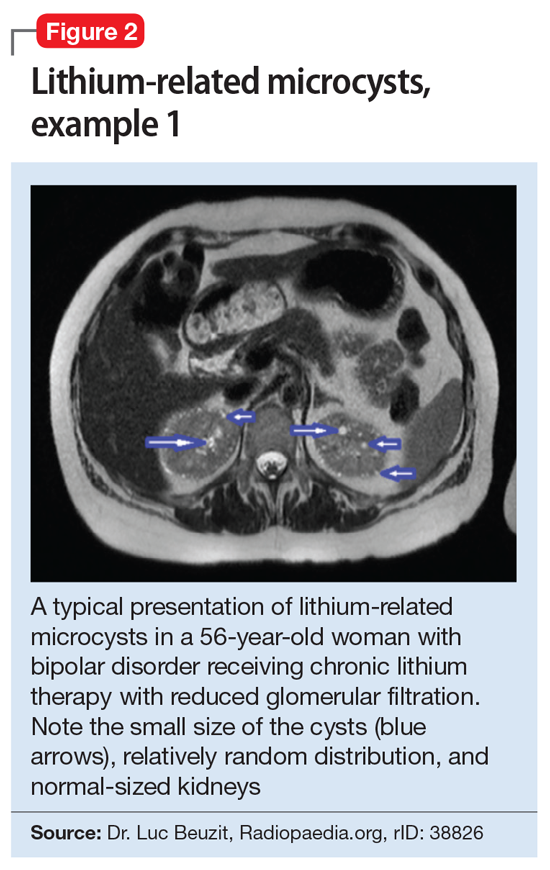

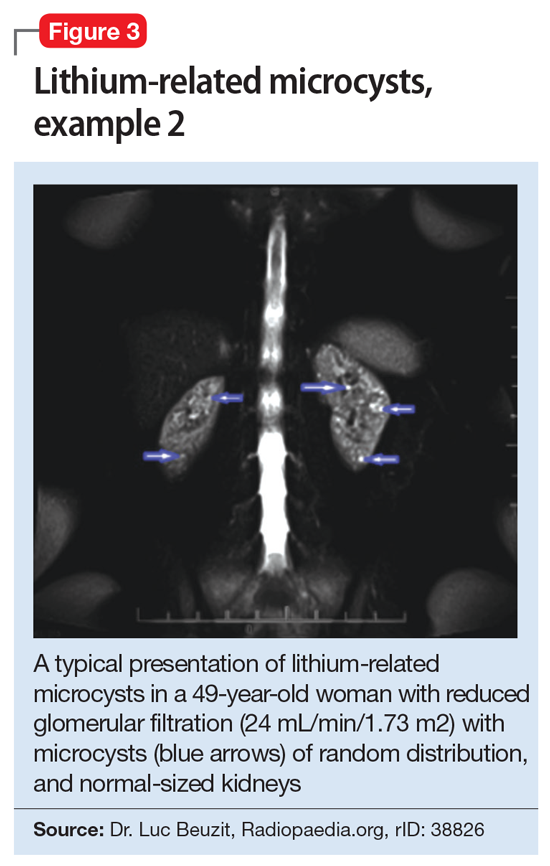

This association appears to be sufficiently reliable and clinicians can use T2-weighted MRI to determine if renal dysfunction is related to lithium. Lithium-related renal microcysts are visualized as multiple bilateral hyperintense foci with a diameter of 1 to 3 mm that involve both the cortex and medulla, tend to be symmetrically distributed throughout the kidney, and are associated with normal-sized kidneys.33,36 Large cysts are unlikely to be related to lithium; only microcysts are associated with lithium treatment. For examples of how these cysts appear on MRI, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3. The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear, but may be related to the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway or GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta) (Box6,37-44).

Box 1

The exact mechanism of lithium-related nephrotoxicity is unclear. The mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway is an intracellular signaling pathway important in controlling cell proliferation and cell growth via the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Researchers have hypothesized that the mTOR pathway may be responsible for lithium-induced microcysts.38 One study found that mTOR signaling is activated in the renal collecting ducts of mice that received long-term lithium.38 After the same mice received rapamycin (sirolimus), an allosteric inhibitor of mTOR, lithium-induced proliferation of medullary collecting duct cells (microcysts) was reversed.38

Additionally, GSK-3beta (glycogen synthase kinase-3beta), which is expressed in the adult kidney and is a target for lithium, appears to have a role in this pathology. GSK-3beta is involved in multiple biologic processes, including immunomodulation, embryologic development, and tissue injury and repair. It has the ability to promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation.39 At therapeutic levels, lithium can inhibit GSK-3beta activity by phosphorylation of the serine 9 residue pGSK-3beta-s9.40 This action is believed to play a role in lithium’s neuroprotective properties, specifically through inhibiting the proapoptotic effects of GSK-3beta.41,42 Ironically, this antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium may be associated with its renal adverse effects.

Researchers have proposed that lithium enters distal nephron segments, inhibiting GSK-3beta and disrupting the balance between proliferative and apoptotic signals. The appearance of microcysts may be related to lithium’s antiapoptotic effect. In patients who received chronic treatment with lithium, their kidneys displayed multiple cortical microcysts immunopositive for GSK-3beta.43 Lithium may prevent the clearance of older renal tubular cells that would typically have been removed by normal apoptotic processes.37 As more of these tubular cells accumulate, they invaginate and form a cyst.37 As cysts accumulate during 20 years of treatment, the volume that the cysts occupy within the normal-sized and unyielding renal capsule displaces and injures otherwise healthy renal tissue, in a process similar to injury due to hydrocephalus in the brain.37

Interestingly, if the antiapoptotic mechanism of lithium-induced microcysts is true, it is possible that mood stabilizers that also have antiapoptotic properties (such as valproic acid) would also increase the risk of renal microcysts.44 This may underlie the observation that nearly one-half of patients continue to experience progression of renal disease after discontinuing lithium.6

Take-home points

In patients receiving chronic lithium treatment, it can take 20 years to produce a significant reduction in GFR. Switching patients who respond to lithium to other mood-stabilizing agents is associated with a significantly increased risk for mood recurrence and adverse consequences from the alternate medication. Because ESRD may occur more frequently in patients with mood disorders than in the general population, renal disease may be misattributed to lithium use. In approximately one-half of patients, renal disease will continue to progress after discontinuing lithium, which essentially eliminates the benefit of switching medications. This means that the decision to switch a patient who has responded well to lithium treatment for a decade or more to an alternate agent to avoid progression to ESRD may be associated with a very high potential cost but limited benefit.

One solution might be to more accurately identify patients with lithium-related glomerular disease, so that the potential benefit of switching may outweigh potential harm. The presence of renal microcysts on MRI of the kidney may be used to provide some of that reassurance. On renal biopsy, >60% of patients will have documented microcysts, and on MRI, it may approach 100%. The presence of microcysts provides potential evidence that reduced glomerular function is related to lithium. However, the absence of renal microcysts may not be as instructive—a negative MRI of the kidneys may not be sufficient evidence to rule out lithium as the culprit.

Continue to: Bottom Line