- Start by determining whether pain is located in the anterior, lateral, or posterior hip. As the site varies, so does the etiology.

- Besides location, consider sudden vs insidious onset, motions and positions that reproduce pain, predisposing activities, and effect of ambulation or weight bearing.

- Physical examination tests that elucidate range of motion, muscle strength, and pain replication will narrow the diagnostic search.

- Magnetic resonance imaging is usually diagnostic if plain x-rays and conservative therapy are ineffective.

- Conservative measures and selective use of injection therapy are usually effective.

Given the number of disorders capable of causing hip pain, and the fact that hip pathology can refer pain to other areas, and pathology elsewhere (particularly the lumbar spine) can refer pain to the hip,* a useful starting point in the evaluation is one that begins to narrow the search immediately.

*Medial groin pain is often included in the discussion of hip pain, but this topic is beyond the scope of this review.

In the work-up of hip pain, the first fact to establish is whether pain is felt in the anterior, lateral, or posterior part of the hip. Each location suggests a distinctive set of possible underlying causes. We provide diagnostic algorithms for all 3 scenarios, to aid in determining the best course for the work-up.

Anterior hip pain

Anterior hip pain (Figure 1), which is the most common, usually indicates pathology of the hip joint (ie, degenerative arthritis), hip flexor muscle strains or tendonitis, and iliopsoas bursitis. In a study by Lamberts and colleagues,5 by far the most common diagnosis of patients with hip complaints seen by their general practitioner was osteoarthritis. In a study of subjects older than 40 years who experienced a new episode of hip pain, 44% had evidence of osteoarthritis (level of evidence [LOE]=1b).6

Iliopsoas bursitis, a less common cause of anterior hip pain, involves inflammation of the bursa between the iliopsoas muscle and the iliopectineal eminence or “pelvic brim (Figure 2).

Stress fractures typically occur in athletes as the structural demands from training exceed bone remodeling (fatigue fractures), and may also occur in the setting of osteoporosis under normal physiologic loads (insufficiency fractures).

Labral tears have recently been recognized in younger athletic patients with unexplained hip joint pain and normal radiographic findings.7

FIGURE 1

Evaluating anterior hip pain

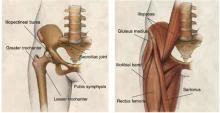

FIGURE 2

Hip joint

Anatomy of the hip joint and surrounding musculature.

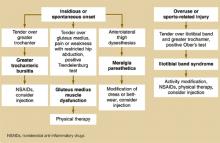

Lateral hip pain

Lateral hip pain (Figure 3) is usually associated with greater trochanteric pain syndrome, iliotibial band syndrome, or meralgia paresthetica.

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is a relatively new term that includes greater trochanteric bursitis and gluteus medius pathology.8,9 Trochanteric bursitis is a common cause of lateral hip pain, especially in older patients. However, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study of 24 women with greater trochanteric pain syndrome (described as chronic pain and tenderness over the lateral aspect of the hip) found that 45.8% had a gluteus medius tear and 62.5% had gluteus medius tendonitis, calling into question how many of these patients actually have bursitis (LOE=4).9

Iliotibial band syndrome is particularly common in athletes. It is caused by repetitive movement of the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter.

Meralgia paresthetica, an entrapment syndrome of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, is another cause of lateral hip pain that occurs more frequently in middle age. Meralgia paresthetica is characterized by hyperesthesia in the anterolateral thigh, although 23% of patients with this disorder also complain of lateral hip pain.10

FIGURE 3

Evaluating lateral hip pain

Posterior hip pain

Posterior hip pain (Figure 4) is the least common pain pattern, and it usually suggests a source outside the hip joint. Posterior pain is typically referred from such disorders of the lumbar spine as degenerative disc disease, facet arthropathy, and spinal stenosis. Posterior hip pain is also caused by disorders of the sacroiliac joint, hip extensor and external rotator muscles, or, rarely, aortoiliac vascular occlusive disease.

The family physician in a typical practice can expect to see a patient with hip pain every 1 to 2 weeks, given that this complaint accounts for 0.61% of all visits to family practitioners, or about 1 in every 164 encounters.1 However, few studies shed light on the prevalence of hip disorders, and no clear consensus exists on this matter or even on terminology. Most information about causes of hip pain is drawn from expert opinion in a range of disciplines, including orthopedics, sports medicine, rheumatology, and family medicine.

Runners report an average yearly hip or pelvic injury rate of 2% to 11%.2 In the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 14.3% of patients aged 60 years and older reported significant hip pain on most days over the previous 6 weeks.3 Older women were more likely to report hip pain than older men. NHANES III also reported that 18.4% of those who had not participated in leisure time physical activity during the previous month reported severe hip pain as opposed to 12.6% of those who did engage in physical activity.

In younger patients, sports injuries about the hip and pelvis are most common in ballet dancers, soccer players, and runners (incidence of 44%, 13%, and 11% respectively).4