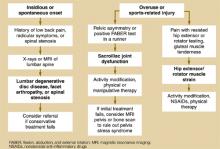

FIGURE 4

Evaluating posterior hip pain

Integrating history and physical examination

Little research has been performed to clarify the sensitivity and specificity of most history and physical examination maneuvers used in the diagnosis of hip pain. Therefore, much of the evaluation of hip pain is based on level 5 evidence: expert opinion.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons created a clinical guideline on the evaluation of hip pain.11 Although a useful resource, this guideline focuses primarily on 3 diagnoses—osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, and avascular necrosis—and does not expand upon the many other causes of hip pain that present to a primary care physician. Based on the available literature as well as our experience, we recommend the following approach to a patient with hip pain.

Medical history

After identifying whether the pain is anterior, lateral, or posterior (Figure 1, (Figure 3), and (Figure 4), focus on other characteristics of the pain—sudden vs insidious onset, movements and positions that reproduce the pain, predisposing activities, and the effect of ambulation or weight-bearing activity on the pain (Table 1).

In general, osteoarthritis and trochanteric bursitis are more common in older, less active patients, whereas stress fractures, iliopsoas strain or bursitis, and iliotibial band syndrome are more common in athletes. Complaints of a “snapping sensation may indicate iliopsoas bursitis if the snapping is anterior, or iliotibial band syndrome if the snapping is lateral.

Warning signs for other conditions. With any adult who has acute hip pain, be alert for “red flags that may indicate a more serious medical condition as the source of pain. Fever, malaise, night sweats, weight loss, night pain, intravenous drug abuse, a history of cancer, or known immunocompromised state should prompt you to consider such conditions as tumor, infection (ie, septic arthritis or osteomyelitis), or an inflammatory arthritis. Consider appropriate laboratory studies such as a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein; and expedited imaging, diagnostic arthrocentesis, or referral. Fractures must also be excluded if there is a history of significant trauma, fall, or motor vehicle accident.

TABLE 1

Integrating the history and physical examination to diagnose hip pain

| Disorder | Presentation and exam findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior pain | Osteoarthritis | Gradual onset anterior thigh/groin pain worsening with weight-bearing |

| Limited range of motion with pain, especially internal rotation (LOE=1b)12 | ||

| Abnormal FABER test | ||

| Hip flexor muscle strain/tendonitis | History of overuse or sports injury | |

| Pain with resisted muscle testing | ||

| Tenderness over specific muscle or tendon | ||

| Iliopsoas bursitis | Anterior pain and associated snapping sensation | |

| Tenderness with deep palpation over femoral triangle | ||

| Positive snapping hip maneuver | ||

| Etiology from overuse, acute trauma, or rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Hip fracture (proximal femur) | Fall or trauma followed by inability to walk | |

| Limb externally rotated, abducted, and shortened | ||

| Pain with any movement | ||

| Stress fracture | History of overuse or osteoporosis | |

| Pain with weight-bearing activity; antalgic gait | ||

| Limited range of motion, sensitivity 87% (LOE=4)13 | ||

| Inflammatory arthritis | Morning stiffness or associated systemic symptoms | |

| Previous history of inflammatory arthritis | ||

| Limited range of motion and pain with passive motion | ||

| Acetabular labral tear | Activity-related sharp groin/anterior thigh pain, esp. upon hip extension | |

| Deep clicking felt, sensitivity 89% (LOE=4)14 | ||

| Positive Thomas flexion-extension test | ||

| Avascular necrosis of femoral head | Dull ache in groin, thigh, and buttock usually with risk factors (corticosteroid exposure, alcohol abuse) | |

| Limited range of movement with pain | ||

| Lateral pain | Greater trochanteric bursitis | Female:male 4:1, fourth to sixth decade |

| Spontaneous, insidious onset lateral hip pain | ||

| Point tenderness over greater trochanter | ||

| Gluteus medius muscle dysfunction | Pain with resisted hip abduction | |

| Tender over gluteus medius (cephalad to greater trochanter) | ||

| Trendelenburg test: sensitivity 72.7%, specificity 76.9% for detecting gluteus medius muscle tear (LOE=2b)9 | ||

| Iliotibial band syndrome | Lateral hip pain or snapping associated with walking, jogging, or cycling | |

| Positive Ober's test | ||

| Meralgia paresthetica | Numbness, tingling, and burning pain over anterolateral thigh | |

| Aggravated by extension of hip and with walking | ||

| Pressure over nerve may reproduce dysesthesia in distribution of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LOE=5)15 | ||

| Posterior pain | Referred pain from lumbar spine | History of low back pain |

| Pain reproduced with isolated lumbar flexion or extension | ||

| Radicular symptoms or history consistent with spinal stenosis | ||

| Sacroiliac joint dysfunction | Controversial diagnosis | |

| Posterior hip or buttocks pain usually in runners | ||

| Pelvic asymmetry found on exam | ||

| Hip extensor or rotator muscle strain | History of overuse or acute injury | |

| Pain with resisted muscle testing | ||

| Tender over gluteal muscles | ||

| LOE, level of evidence. For an explanation of levels of evidence. | ||

Physical examination

Begin your examination by observing the patient's gait and general ability to move around the examining room.

Range of motion. Carefully assess range of motion of the hip, comparing the affected side with the normal side to detect subtle limitations or painful movements. Range of motion testing includes passive hip flexion, internal and external rotation, and the flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABER) test (Figure 5).

In the FABER test, the patient lies supine; the affected leg is flexed, abducted, and externally rotated. Lower the leg toward the table. A positive test elicits anterior or posterior pain and indicates hip or sacroiliac joint involvement.