Thus, using insulin glargine as basal insulin allows patients to reach recommended targets with fewer episodes of hypoglycemia, and can help address patients’ fear that can be a barrier to initiating insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes. Two recent studies have reported that dosing of insulin glargine can be flexible—morning or bedtime administration yields comparable low rates of hypoglycemia.30,31

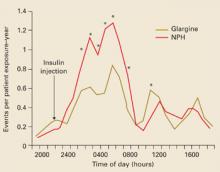

FIGURE 3

Hourly hypoglycemia rate with glargine much less than with NPH

*P<.05 (between treatment).

Copyright © 2003 American Diabetes Association. From Diabetes Care 2003; 26:3080–3086.29 Reprinted with permission from American Diabetes Association.

Basal insulin plus prandial insulin

For patients who cannot otherwise reach Hb A1c goals, basal insulin therapy may be supplemented with prandial insulin. Newer, rapid-acting analogs used for the prandial component are insulin lispro, insulin glulisine, or insulin aspart. Although this approach is physiologically more rational than regimens using conventional insulins, data are limited for use in type 2 diabetes.

The incidence of nocturnal hypoglycemia was evaluated in a study of patients with type 1 diabetes and impaired hypoglycemic awareness who were treated with 1 of 2 regimens: insulin lispro in a basal-prandial combination with NPH insulin, or twice-daily, premixed NPH/regular insulin.33 Results showed that the incidence of nocturnal hypoglycemia was lower in patients receiving the insulin lispro regimen.

Another study, comparing insulin aspart and regular insulin as the prandial component in a basal-prandial regimen with NPH, showed that postprandial glucose control and Hb A1c levels were significantly better after 1 year of treatment in the insulin aspart group than in the group receiving regular insulin, without an increased risk for hypoglycemia.34 These results suggest that treatment with rapidacting insulin analogs could be helpful in avoiding hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes when a basal-prandial insulin regimen is indicated.

Avoiding hypoglycemia in the elderly

Elderly patients may be at increased risk for iatrogenic hypoglycemia. A populationbased study of patients presenting to an emergency room with severe hypoglycemic symptoms reported that rates of such events among elderly patients with type 2 diabetes and multiple comorbidities approached the rates among patients with type 1 diabetes.35

Creatinine clearance is often decreased in elderly patients, slowing elimination of oral agents and insulin and potentially resulting in sustained pharmacological action and creating a greater risk for hypoglycemia.

Furthermore, there is evidence that the neurogenic symptoms of hypoglycemia are reduced in elderly patients, diminishing awareness of hypoglycemia.36

In the demented elderly, malnutrition, weight loss, and anorexia may exacerbate the risk for hypoglycemia. For elderly patients with tertiary disease (eg, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, blindness, chronic renal failure), the risk for hypoglycemia and subsequent comorbidity may outweigh the benefits of strict glycemic control.3,37 Elderly patients may have comorbid conditions that increase risk of falls (eg, poor vision, neurologic conditions), and hypoglycemic episodes may further increase the risk of falls and lead to morbidity (eg, fragility fracture in patients with osteopenia or osteoporosis).

Because the elderly are at a greater risk for hypoglycemia, a switch to a less restrictive diet, such as a “no concentrated sweets” diet, is an option, with control of glucose levels through the administration of oral agents or insulin.36 This may also promote a better quality of life, considering that many of these patients already have secondary and tertiary complications of diabetes, prevention of which is not a realistic goal.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

William Cefalu, MD, Professor and Chief, Division of Nutrition and Chronic Diseases, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University, 6400 Perkins Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70808. Email: cefaluwt@pbrc.edu