Patient evaluation

Figure 1 is an algorithm that outlines steps in the evaluation and management of patients who experience tinnitus. The first step is to collect as much information as possible about the patient and his condition.

FIGURE 1

Evaluation and management of tinnitus

Tinnitus history

Determine the duration of tinnitus and whether circumstances such as upper respiratory infection, otalgia, noise exposure, head trauma, sudden hearing loss, or vertigo occurred at the time of tinnitus onset. Ask the patient to describe the tinnitus: Is it intermittent or constant? High- or low-pitched? Unilateral or bilateral? Pulsatile or steady?

Unilateral tinnitus and hearing loss provide preliminary evidence for acoustic neuroma or cerebrovascular accident. High-pitched tinnitus is usually associated with high-frequency hearing loss caused by presbycusis (hearing impairment in the aged) or excessive noise exposure. Low-pitched roaring tinnitus is sometimes associated with low-frequency hearing loss exhibited by patients with Meniere’s disease. Pulsatile tinnitus, especially if synchronous with the patient’s pulse, can indicate vascular abnormalities.

Ask the patient if fatigue, stress, noise exposure, or any medications exacerbate the tinnitus. Also ask if masking sounds (such as water running in the shower), medications, or any other factors provide relief from tinnitus. This information can be used to formulate a tinnitus management program.

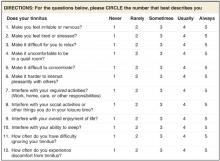

Assess the severity of the patient’s tinnitus using an instrument such as the Tinnitus Severity Index (Figure 2).11 A score of 36 or higher indicates bothersome tinnitus (level of evidence [LOE]: 2).12 Higher scores indicate that patients perceive their tinnitus to be a significant, even debilitating problem.

FIGURE 2

Tinnitus Severity Index

Hearing history

If possible, determine the presence and type of hearing loss (congenital, sudden, sensorineural, conductive, or mixed). Note the patient’s history of ear infections, surgeries, noise exposure (occupational or recreational), otalgia, otorrhea, and vertigo or other balance problems. Ask whether immediate family members have experienced hearing loss or tinnitus.

Health history

Look particularly for conditions that can contribute to hearing loss and tinnitus, such as hypertension, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, arteriosclerosis, and autoimmune disorders (eg, lupus or rheumatoid arthritis). Also consider ototoxic medications, such as aminoglycoside antibiotics, cisplatin, furosemide, valproic acid, and high doses of quinine-containing compounds. When possible, patients with hearing loss or tinnitus should be given alternative medications free from ototoxicity.

Excessive use of alcohol, caffeine, and aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can exacerbate tinnitus for some patients. However, moderate use of these products is often possible.

Psychosocial history

Inquire about the patient’s marital and occupational status. Unemployed patients living alone often perceive tinnitus to be more severe than do employed patients who have supportive social networks. Also ask about any history of insomnia, anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or psychosis. A questionnaire such as the abbreviated Beck Depression Inventory13 can be used to assess the presence and severity of depression.

Physical exam and testing

Patient evaluation should include the following physical examinations and tests.

Otolaryngologic/head and neck exam. Otoscopic examination can detect infections such as otitis media, which will usually be accompanied by complaints of ear pain or fullness, and possibly hearing loss in combination with tinnitus. Otoscopy can also detect impacted earwax (cerumen), which can occlude the ear canal or cause immobilization of the tympanic membrane, resulting in conductive hearing loss, tinnitus, and a feeling of fullness in the ear. Symptoms usually resolve when the earwax is removed.

If the tinnitus is synchronous with the patient’s pulse, it suggests a vascular contribution for the symptom. Auscultation of blood vessels in the neck can reveal venous hums or other types of bruits audible to the patient. Venous hum can be diagnosed by temporarily blocking blood flow through the jugular vein on the side where tinnitus is perceived.

Neurologic exam. A complete neurologic exam should include the Romberg test, Dix-Hallpike maneuver (if the patient experiences vertigo), gait testing, and cranial nerve function tests.

Audiologic testing. Audiologic tests should include pure tone air and bone conduction thresholds, speech discrimination testing, tympanometry, and most comfortable loudness (MCL) and uncomfortable loudness level (UCL) tests. Tympanometry is used to assess middle-ear function. Abnormal tympanograms and significant differences between air and bone conduction thresholds can indicate otitis media, otosclerosis, or cholesteatoma.

MCL and UCL tests are used to assess the dynamic range of patients’ hearing. Patients with UCLs that are only 5 to 20 dBs above their MCLs have a reduced dynamic range of hearing that can be caused by recruitment or hyperacusis. The audiometer can also be used to match the tinnitus for pitch and loudness and to test the effects of masking sounds on the patient’s tinnitus.