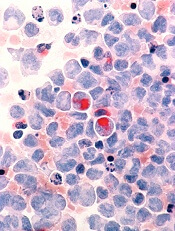

Credit: Lance Liotta

Researchers have found evidence to suggest that methylation patterns in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) can be used to determine prognosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The team discovered that patients with methylation patterns resembling those of healthy individuals lived longer than patients with substantially different patterns.

If validated in clinical trials, this finding could be used to help physicians tailor treatment according to a patient’s needs.

Ulrich Steidl, MD, PhD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, and his colleagues described this research in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The investigators knew that aberrations in HSC methylation can prevent the cells from differentiating into mature blood cells, which leads to AML.

So they speculated that comparing how closely the methylation patterns in cells from AML patients resemble the patterns found in healthy individuals’ HSCs might foretell the patients’ response to treatment.

To find out, the researchers first looked at methylation patterns in HSCs from healthy individuals. The team found that most cytosines are methylated in healthy HSCs.

And where demethylation occurs, it’s mainly limited to one particular stage of HSC differentiation—the commitment step from short-term HSC to common myeloid progenitor.

The investigators then set out to identify loci with the most significant methylation changes across differentiation stages. Their analysis revealed a set of 561 loci that distinguished between the 4 stages of HSC development they investigated.

The team next wanted to determine whether the methylation status of these loci was affected in AML. So they developed an epigenetic signature score based on loci methylation. A patient’s score increased the more his methylation pattern differed from that of a healthy individual.

The researchers tested their scoring method using data from 3 cohorts of AML patients. In each of these groups, patients with low scores had approximately twice the median survival time of patients with high scores.

Specifically, the investigators evaluated AML patients in a trial testing 2 different doses of daunorubicin (Fernandez et al, NEJM 2009).

Among patients receiving lower-dose daunorubicin, those with lower epigenetic signature scores had a median overall survival (OS) of 19 months, compared with 10.8 months for patients with higher scores (P=0.0165).

The researchers observed similar results in the patients receiving a higher dose of daunorubicin. The median OS in the group with low epigenetic signature scores was 25.4 months, compared with 13.2 months in the group with high scores (P=0.0062).

Likewise, in a third cohort of AML patients, those with a low epigenetic signature score had significantly better OS than those with a high score—a median of 28.1 months and 14.9 months, respectively (P=0.0150).

The investigators performed the same analyses using a commitment-associated gene-expression signature. And they found their epigenetic signature was more effective at predicting patient survival.

Dr Steidl and his colleagues are now studying the genes found in the aberrant epigenetic signatures to determine if they play a role in causing AML.